United Students Against Sweatshops' Statement

April 15, 2005

Cal-Safety Compliance Corporation is Not a Credible Monitor for Coca-Cola's Labor Practices

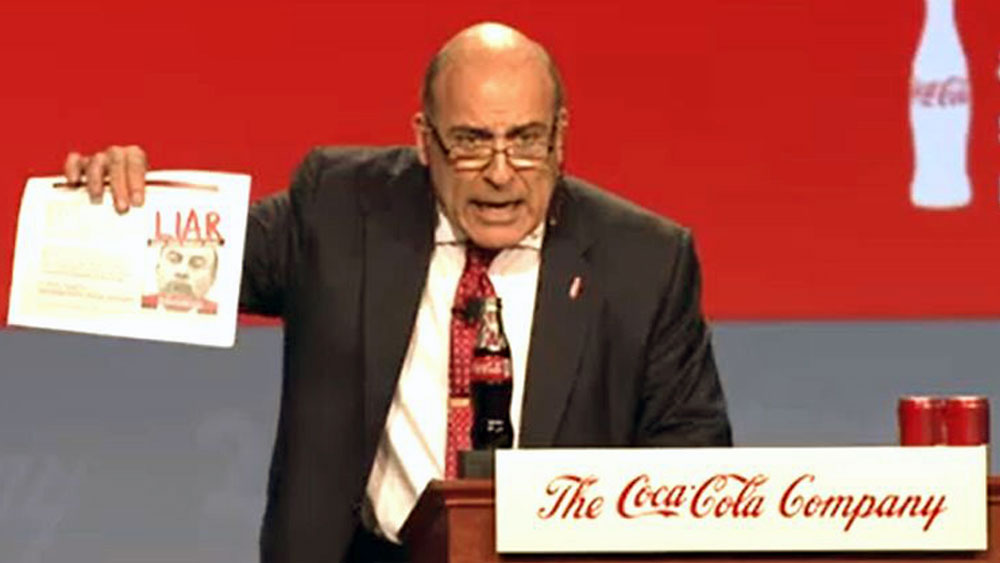

The Coca-Cola Company has recently released a report by the for-profit corporation Cal-Safety Compliance Corporation as an "independent investigation" of Coca-Cola's labor practices in Colombia. This is a public relations move in anticipation of the huge protests that will happen at Coca Cola's shareholder meeting on April 19th as well as increasing student pressure on campuses throughout the nation.

We want to make clear that we view this development as entirely unacceptable and unviable as a means of moving forward the process of ensuring that workers' rights are respected in Coca-Cola bottling facilities in Colombia.

Cal-Safety is not regarded as a credible monitoring organization within the mainstream worker rights advocate community as result of its track record of missing egregious violations in high profile cases and its flawed monitoring methodology. This investigation by Cal-Safety funded by Coca-Cola will not be taken seriously by the anti-sweatshop movement and does not put to rest our long standing concern about human rights abuses in Coca-Cola's plants in Colombia.

The document provides some background that informs our view of Cal-Safety and why the company cannot be relied upon to find, report, and correct worker rights violations in this case.

Cal-Safety and the Case of El Monte

Cal-Safety is perhaps best known among worker advocates for its role in the case of El Monte, the most infamous incident of sweatshop abuse in modern American history. In this case, 75 women 5 men were kept in conditions resembling slavery in a factory compound located in El Monte, California. For up to five years, the workers were forbidden to leave the compound, forced to work behind razor wire and armed watch, sewing garments for top American brands for less than a dollar an hour. The workers worked from 7:00 am until midnight, seven days a week. Eight to ten people were forced to live in rat infested rooms designed for two.[1]

Cal-Safety was the registered monitor for the front shop, D&R. D&R transferred hundreds of bundles of cut cloth to the slave sweatshop and delivered thousands of finished garments to manufacturers and retailers each day, yet there were fewer than a dozen sewing machines at the D&R facility. Cal-Safety's inspection of the facility failed to uncover anything unusual, including the large volume of work being sent out to the slave sweatshop. In addition, Cal-Safety even failed to identify the numerous wage and hour violations of the 22 Latino workers employed by the D&R facility.[2] The revelations of abuse at the El Monte factory was a major event in American labor history, helping to spark the modern anti-sweatshop movement. The failure of Cal-Safety to find abuses in this case is one of the most widely cited examples of the shortcomings of the private monitoring industry.

Additional Incidents of Ineffective Monitoring by Cal-Safety

As a result of its failure to identify violations in the El Monte case, Cal-Safety was the subject of extensive public criticism. However, even with this criticism, Cal-Safety's auditing practices continued to be exposed as inadequate. The following are additional high profile cases in which Cal-Safety failed to find and/or report worker rights violations.

§ In 1998, Cal-Safety gave Trinity Knitworks, a garment factory in Los Angeles, a clean report despite the fact that the factory failed to provide complete records and had failed to pay employees for months. Cal-Safety reported to Disney, its client in this case, that Trinity was fully compliant with labor standards at nearly the same moment that investigators of the California Department of Labor were investigating the factory and citing it with massive minimum wage violations, including $213,000 in back wages owed to some 142 workers.[3] In September, 1998, when the Department of Labor seized 17,000 Disney garments from Trinity, the factory's checks to workers had been bouncing for five months. Cal-Safety had visited the factory during this period. A December 1, 1998 Los Angeles Times article reported that "as representatives of Disney and the other firms kept close watch over production details, such as the placement of inseams, hemlines and zippers, monitors hired by the companies failed to notice Trinity workers were not being paid." The article goes on to quote Joe A. Razo, California's deputy labor commissioner, who said, "You'd have to be pretty blind not to know what was happening at Trinity."[4]

§ In 1999, Cal-Safety was the monitor hired by John Paul Richard, a high-end garment manufacturer producing in Los Angeles. Cal-Safety failed to identify and report sweatshop conditions, including falsified time records, off-the-clock work and sub-minimum wages. In fact, following a visit from a Cal-Safety inspector, two Latino garment workers who had spoken to Cal-Safety were fired in the presence of factory managers. When Cal-Safety was contacted about this act of retaliation for cooperating with a monitor, Cal-Safety refused to do anything, insisting that it wasn't Cal-Safety's problem. After the workers filed a federal lawsuit against the manufacturers and retailers in that case, formal discovery of Cal-Safety revealed a thoroughly inadequate process for training, inspecting and reporting.[5]

§ In 1999, Cal-Safety was hired by Wal-Mart to audit a factory in China called Chun Si which produced handbags for Wal-Mart's Kathy Lee Gifford line. As revealed in a lengthy expose by Business Week, the factory kept workers in virtual captivity, locked in the walled in compound for twenty three hours a day. Management confiscated workers' identify guards, placing them in danger of deportation if they left the factory. Factory guards routinely beat workers for talking back to managers or walking too slow.

Workers were fined as much as one dollar for infractions as minor as spending too long in the restroom. Cal-Safety, along with Price Waterhouse Coopers, audited the factory five times. Business Week reported that, while Cal-Safety's audits found some of the less serious violations regarding unpaid and excessive overtime, Cal-Safety's "audits missed the most serious abuses including beatings and confiscated identity papers."[6]

Cal-Safety's Flawed Monitoring Methodology

Information about the above examples of Cal Safety's monitoring track record is complemented by the results of a thorough investigation into Cal Safety's monitoring methodology by Dr. Jill Esbenshade, presented in the recently released book, "Monitoring Sweatshops." In her research, Esbenshade conducted extensive interviews with Cal-Safety auditors and directly observed the company's labor auditing in practice. Given the problematic practices documented, Cal-Safcty's poor track record is perhaps not surprising. In numerous key areas, Cal Safety failed to adhere to minimum accepted standards for competent factory investigation.

• Unannounced factory visits have been shown to be substantially more effective in identifying worker rights violations, because they deny management the opportunity to hide abuses. Yet the majority of Cal-Safety's factory audits are announced, meaning that factory management has full knowledge that the auditors will be visiting the factory on the appointed date and time.[7]

• The process of identifying, documenting, reporting, and correcting worker rights abuses is a difficult and labor intensive process. Department of Labor investigations take roughly 20 hours to complete. WRC investigations often take hundreds of person hours over a period of months. However, Cal-Safety purports to accomplish the same work in just a few hours. Cal-Safety factory audits are generally scheduled every three hours, including time to commute to a new site or take a lunch or rest break, meaning that audits frequently take substantially less than three hours.[8]

• It is well established that interviewing workers outside of the factory in locations workers choose is far more effective in getting candid information about working conditions than interviewing workers inside of the factory where managers know who is being interviewed and workers can become the subjects of reprisal and retaliation. Yet, according to Cal-Safety auditors, Cal-Safety primarily conducts worker interviews on the factory floor or in an office in the factory. A former Cal-Safety monitor said, "There is no privacy in the conversation. The employer knew who was being interviewed." [9]

• The key area of concern in Coca-Cola's bottling facilities is freedom of association and the right of workers to unionize and bargain collectively, and thus expertise in this area is critical to an effective investigation. Yet Cal-Safety does not consider collective bargaining rights or freedom of association to be within the purview of its audits in the United States, and does not investigate for violations of the National Labor Relations Act. At the Cal-Safety office, researchers noticed anti-union propaganda posted on the wall voicing the message that monitoring is a substitute for unionization.[10] No evidence could be found indicating that Cal-Safety has experience or expertise investigating violations of associational rights overseas.

• A basic principle of credible monitoring is that organizations that are beholden to the industry they monitor as their principle source of income are not likely to produce reports that are entirely unbiased or critical of their paymaster. However, Cal-Safety has been contracted and paid directly by many of the world's largest corporations, including Wal-Mart, Walt Disney, the Gap, and Nike.[11] Cal-Safety's annual revenue through private for-profit monitoring is in the millions of dollars.[12] Corporate contracts are its principle source of income.

• A basic principle of the University's anti-sweatshop policy is transparency and the public disclosure of factory information a practice to which Cal-Safety has never submitted itself. Cal-Safety does not publicly disclose its monitoring reports to the public or to the workers whom the audits are supposedly designed to benefit. Even the names and locations of factories are a strictly held secret. Indeed, Cal-Safety's website states, "CSCC considers all of its monitoring interactions to be extremely confidential; inspection data is strictly controlled and released only to the client of record." [13]

Conclusion

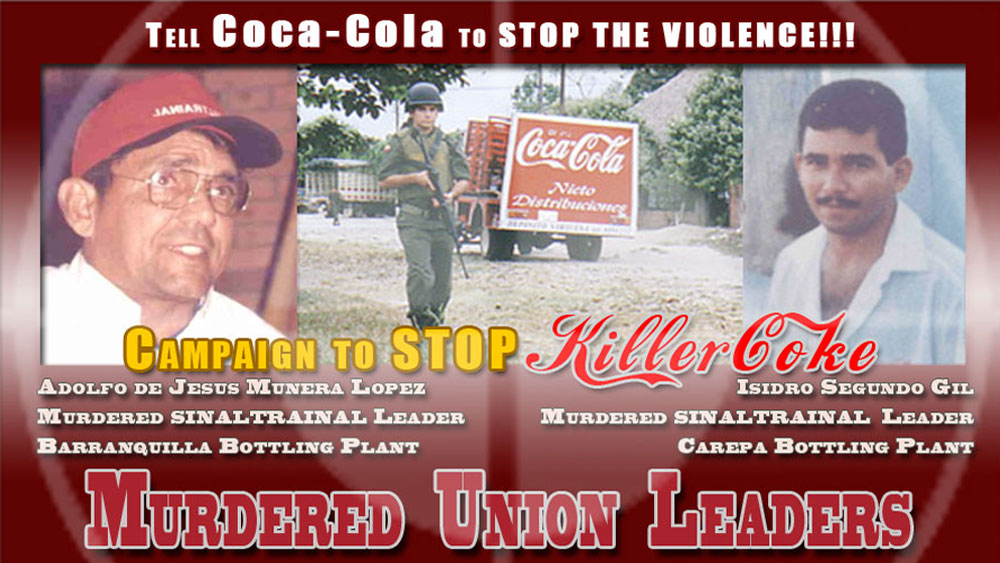

In sum, based upon the information available, there are ample grounds to conclude the Cal-Safety is unfit to monitor Coca-Cola's labor practices in Colombia. Indeed, given its repeated failure to find egregious violations in high profile cases of worker abuse, its status as a for-profit corporation, its practice of monitoring generating revenue from the major corporations for whom it monitors, its lack of experience with the core issue of freedom of association, its flawed methodology in visiting factories and conducting worker interviews, and its utter lack of transparency, Cal-Safety should easily be ruled out as a candidate for credibly investigating the case of Coca-Cola in Colombia.

We expect that if Cal-Safety does conduct a paid audit of Coca-Cola's practices, the most likely outcome will be that it finds minor violations sufficient to slap Coca-Cola on the wrist but fails to adequately investigate and report on the serious violations, involving violence and the threat of violence against trade unionists, that have prompted worldwide concern.

The University should not lend its credibility or place any credence in this transparent effort to whitewash a serious case of human rights abuse.

[1] For a detailed account of the El Monte case, see Robert Ross et al. 1997. No Sweat: Fashion, Free Trade and the Rights of Garment Workers.

[2] Hearing before the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations of the Committee of Education and the Workforce, California House of Representatives, May 18, 1998. Statement of Julie A. Su, Attorney, Asian Pacific Legal Center

[3] Patrick McDonnell, Los Angeles Times December 1, 1998. ³Industry Woes Help Bury Respected Garment Maker²

[4] Ibid.

[5] Asian Pacific American Legal Center. September 20, 2000. ³Settlement Reached With Major L.A. Garment Manufacturers Who Ignored Reports of Sweatshop Labor²

[6] Business Week, Business News 2 October 2000. "Inside a Chinese Sweatshop: A Life of Fines and Beating"

[7] Esbenshade, Jill. 2004. Monitoring Sweatshops: Workers, Consumers, and the Global Apparel Industry. pg 73

[8] Ibid. pg 72

[9] Ibid. pg 77

[10] Ibid. pg 81

[11] Source: National Labor Committee

[12] Esbenshade, Jill. 2004. Monitoring Sweatshops: Workers, Consumers, and the Global Apparel Industry. pg 65

[13] From Cal-Safety's website