Reports | Monserrate

Campaign Reports | Newletter Archive

Critical Talking Points |

Books |

DVDs |

Lesley Gill Report |

Aaron Bernstein

Harvard Paper |

Higginbottom Report |

Historic Discrimination Settlement: Ingram vs. The Coca-Cola Company |

OFCCP: Racial Discrimination Settlement |

Monserrate Investigation |

Nazi Germany & Coke |

Professor Peter Hutt Harvard Class Paper |

Polaris Institute Report |

War on Want Report |

Judicial Misconduct |

2001 Colombia Complaint |

2006 Colombia Complaint |

2010 Guatemala Complaint |

Bigio vs. Coca-Cola |

Racial Discrimination in Coke Plants

I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In January 2004, New York City Council Member Hiram Monserrate and a delegation of union, student and community activists traveled to Colombia to investigate allegations by Coca-Cola workers that the company is complicit in the human rights abuses the workers have suffered. The delegation met with Coke officials and workers, as well as a variety of governmental, human rights and clergy representatives.

The findings of the New York City Fact-Finding Delegation on Coca-Cola in Colombia support the workers' claims that the company bears responsibility for the human rights crisis affecting its workforce.

To date, there have been a total of 179 major human rights violations of Coca-Cola's workers, including nine murders. Family members of union activists have been abducted and tortured. Union members have been fired for attending union meetings. The company has pressured workers to resign their union membership and contractual rights, and fired workers who refused to do so.

Most troubling to the delegation were the persistent allegations that paramilitary violence against workers was done with the knowledge of and likely under the direction of company managers. The physical access that paramilitaries have had to Coca-Cola bottling plants is impossible without company knowledge and/or tacit approval. Shockingly, company officials admitted to the delegation that they had never investigated the ties between plant managers and paramilitaries. The company's inaction and its ongoing refusal to take any responsibility for the human rights crisis faced by its workforce in Colombia demonstrates-at best- disregard for the lives of its workers.

Coca-Cola's complicity in the situation is deepened by its repeated pattern of bringing criminal charges against union activists who have spoken out about the company's collusion with paramilitaries. These charges have been dismissed without merit on several occasions.

The conclusion that Coca-Cola bears responsibility for the campaign of terror leveled at its workers is unavoidable. The delegation calls on the company to rectify the situation immediately, and calls on all people of conscience to join in putting pressure on the company to do so.

II. DELEGATION HISTORY, PARTICIPANTS AND MANDATE

New York City Council Member Hiram Monserrate and five labor and community activists traveled to Colombia from January 8th through January 18th to investigate allegations by Colombian workers at Coca-Cola bottling plants that Coke is complicit in the violence against union leaders and members. This trip was the result of an investigative process and a dialogue with the company that began almost a year ago.

Monserrate, representing the large and growing Colombian community in Jackson Heights and Elmhurst, Queens, organized the New York City Fact-Finding Delegation on Coca-Cola in Colombia-a coalition of students, human rights activists, and U.S. trade unionists and members of the Colombian immigrant community living in the New York City-to ensure that one of Coca-Cola's largest markets, New York City, is not underwriting labor abuses beyond our borders.

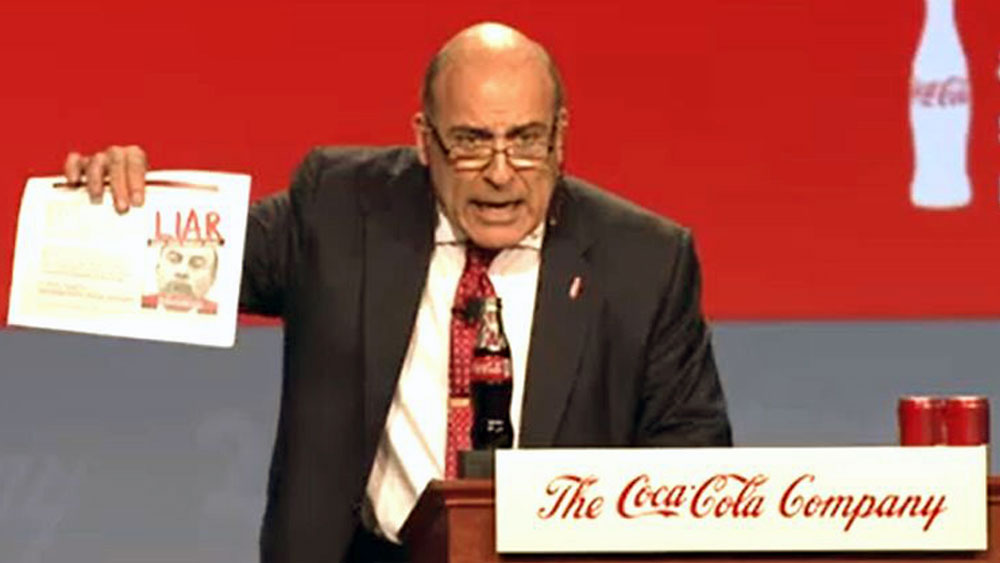

At Monserrate's request, the councilman and others from the delegation met with top Coca-Cola officials in July 2003 to discuss the human rights crisis facing Coke workers in Colombia. During that meeting, company officials testified that the allegations of company ties to the paramilitaries carrying out the violence, threats and intimidation were false.

The delegation asked Coca-Cola to sponsor an independent fact-finding mission to Colombia to investigate and assess the workers' allegations of company involvement in the extra-legal violence against them. Following the July 2003 meeting, Coca-Cola responded in writing that the "Company does not anticipate supporting in any way any form of 'independent fact-finding delegation to Colombia,'" and that allegations would only be reviewed locally. Believing firmly that the matter demanded an investigation, Monserrate and other delegation members then undertook to organize the trip that took place in January 2004.

The delegation participants in that trip were: Monserrate, representing the 21st City Council district in Queens; Dorothee Benz, representing Communications Workers of America (CWA) Local 1180; Lenore Palladino, the national director of United Students Against Sweatshops (USAS); Segundo Pantoja, representing the Professional Staff Congress-City University of New York (PSC-CUNY); Jose Schiffino, representing the Civil Service Employees Association (CSEA); and Luis Castro, assistant and community liaison to Councilman Monserrate.

The New York City Fact-Finding Delegation on Coca-Cola in Colombia's mandate for the January 2004 trip was to investigate the violence against Coca-Cola workers, to talk first hand with officials and workers from the company, and to assess the allegations of company complicity in the violence.

The delegation returned on January 18, and released a preliminary report on January 29. It also initiated follow-up correspondence with the company. Following the release of the initial report, delegation members reviewed the voluminous documentation in the case they had received, and sought additional documentation that had been promised the delegation by the company.

The present report represents a comprehensive review of the material in hand at the time of this writing. The delegation considers the evidence conclusive, though it continues to seek out additional documentation that might shed additional light on the situation.

III. NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT

Colombia is the most dangerous country in the world to be a trade unionist. More unionists are killed in Colombia every year than in the rest of the world combined: 169 in 2001, 184 in 2002, 92 in 2003. In all, some 4,000 union members have been assassinated since 1986, and to date no one has been arrested, tried and convicted for a single one of these murders. In addition to murder, unionists have been subject to other forms of violence and terror, including kidnapping, beatings, death threats and intimidation.

The bulk of the violence is committed by members of paramilitary units, also known as death squads, primarily the Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC). Collusion between the state military and paramilitary forces is an open secret in Colombia, and the total impunity of those who terrorize union activists only underscores the connection between legal and illegal actors seeking to suppress union activity.

Colombia has been in the midst of a civil war for over four decades. Colombian unions are overwhelmingly independent and not involved in the armed struggle of the leftist guerrillas, but they are often branded by the rightist paramilitaries as guerrillas for their advocacy of social justice and social equity. Such accusations are frequently preludes to assassinations and other violence.

The persecution of social justice advocates under the guise of prosecuting terrorists has also given the Colombian government an excuse to curtail the rights and liberties of unions. Unions are increasingly the subject of legal attack as well as extra-legal killings and threats. Changes in Colombian law in 1990 provided the framework for eliminating permanent employment and replacing it with contingent labor, increasing job insecurity and also greatly inhibiting the ability of unions to organize the temporary workers who now form the vast majority of the Colombian workforce. Meanwhile, a series of laws passed in December 2003 reduced social benefits and curtailed labor rights and civil liberties. The infringements on rights were passed as an "anti-terrorist" statute, with arguments now familiar to those of us living in the post-9/11 U.S. The social cuts were in line with IMF "structural adjustment" demands for austerity, as are massive ongoing privatization efforts. Some 30,000 government workers have been fired; the government projects another 40,000 will also lose their jobs.

The result of these trends is that unemployment stands officially at 20% while real unemployment is much higher, and underemployment is higher still. Union density has plummeted from 12% a decade ago to a mere 3.2% now.

Both legal and illegal repression of unions is widely perceived in Colombia as serving the interests of multinational corporations. Indeed, the delegation heard many stories while in Colombia about the collusion between companies and paramilitaries — stories of terror campaigns where thousands were killed or driven off their land by paramilitaries preceding the entry of a multinational company into an area. Thus, the allegations against Coca-Cola about its role in the violence against its workers are typical, rather than exceptional.

Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de Industrias Alimenticias (SINALTRAINAL) is the National Food Workers' Union, which represents Colombia's Coca-Cola employees. In July of 2001, SINALTRAINAL in conjunction with the United Steelworkers of America (USWA) and the International Labor Rights Fund (ILRF) began proceedings in the United States South Eastern District Court in Florida against the Coca-Cola Company and its Colombian subsidiaries. The lawsuit, an Alien Claims Tort Act (ACTA) civil suit filed in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of Florida, No. 01-03208-CIV, on July 21, 2001, alleges that Coca-Cola subsidiaries in Colombia were involved in a campaign of terror and murder towards its unionized workforce through the use of the right wing paramilitary troops of the AUC. Shortly thereafter, Coca-Cola filed charges in Colombian court against the U.S. plaintiffs for slander and defamation and calling for 500 million pesos in compensation.

IV. DATA SOURCES AND COLLECTION

While in Colombia, the delegation went to Bogota, Barranquilla, Barrancabermeja, Cali, and Bugalagrande. It met with Coca-Cola workers that had been victims of violence, intimidation, retaliation and threats, and workers and others who had been witnesses to these actions. The delegation also met with human rights organizations and activists, other unions, community organizations, and a variety of governmental officials. These additional meetings provided context and in some cases independent verification of union's allegations against the company. The delegation videotaped all of the testimony it received from Coca-Cola workers, and upon its return to the U.S., reviewed the entire videotaped documentation in preparation for this report.

Coca-Cola workers and immediate family members that we interviewed included:

Person 1 [anonymous], Barranquilla, January 11

Limberto Caranza, Barranquilla, January 11

Person 2 [anonymous], Barranquilla, January 11

Person 3 [anonymous], Barranquilla, January 11

Person 4 [anonymous], Barranquilla, January 11

Oscar Giraldo, Bogota, January 12

Hernan Manco, Bogota, January 12

William Mendoza, Barrancabermeja, January 14

Jose Domingo Flores, Barrancabermeja, January 14

In addition, the delegation met with national leaders of SINALTRAINAL, in particular Javier Correa, the president of the union, and Edgar Paez, secretary for International Affairs. It received a PowerPoint presentation entitled "Capital Accumulation and Human Rights Violations" that analyzed Coca Cola's corporate structure, economic strategies, labor practices and profits on January 12, and was given a copy for its documentary records. Additionally, we obtained a book detailing Coca-Cola's history in Colombia, Una Delirante Ambicion Imperial, Universo Latino Publicaciones, Bogota, 2003.

On January 13th, the delegation met with two representatives of Coca-Cola/FEMSA1 in Bogota, Juan Manuel Alvarez, Director of Human Resources, and Juan Carlos Dominguez, Manager of Legal Affairs. Delegation members had tried, while still in New York, to arrange visits to Coca-Cola bottling plants. This request was reiterated in the January 13th meeting, and the delegation at that point asked specifically for access to the plant in Barrancabermeja. Company officials flatly refused. In the course of the meeting with Alvarez and Dominguez, they promised to send several pieces of documentation that they referred to. To date, none of this material has been received despite a letter from corporate headquarters in Atlanta testifying that these materials will be provided (Appendix H).

The delegation received information about Coca-Cola's labor practices and the violence against its workers from several other parties as well, helping to provide a larger social, economic, and political context. In Barrancabermeja, the delegation met with CREDHOS, a regional human rights organization, on January 14, and with the Organizacion Femenina Popular, a women's organization, on January 15. In Cali on January 17, it spoke to Diego Escobar Cuellar, a representative of ASONAL JUDICIAL, the association of judicial workers. Escobar provided chilling insight into the problem of impunity, describing in detail the corruption within the judicial system and its increasing ideological alliance with the paramilitaries. "Colombian justice is an oxymoron," he told delegation members.

The delegation also met with a variety of government and political officials with whom it discussed the Coca-Cola situation. These meetings included: Congressmen Wilson Borja and Gustavo Petro; Daniel Garcia Pena, aide to Bogota Mayor Lucho Garzon; members of the executive board of the Frente Social y Politico, a left-wing political party; Cali Mayor Apolinar Salcedo Caicedo; and the City Council of Cali.

At the outset of the trip, the delegation also met with two staff members of the U.S. Embassy, Craig Conway and Stuart Tuttle, who at the time was in charge of Human Rights.

V. FINDINGS

Coca-Cola's employment practices in Colombia, both those within the letter of the law and those in contravention of the law, have had the effect of driving wages, work standards and job security for Coca-Cola workers sharply downward, and simultaneously, of decimating the workers' union, SINALTRAINAL. Both trends are reinforced by the appalling human rights violations that workers have suffered at the hands of paramilitary forces.

The company denies any involvement in the threats, assassinations, kidnappings and other terror tactics, but its failure to protect its workers even on company property, its refusal to investigate persistent allegations of payoffs to paramilitary leaders by plant managers, and its unwillingness to share documentation that might demonstrate otherwise leads the delegation to the conclusion that Coca-Cola is complicit in the human rights abuses of its workers in Colombia.

Employment practices

During the past decade, Coca-Cola has been centralizing production at its Colombian facilities at the same time that it has decentralized its workforce. In doing so, it has closed or consolidated several of its bottling plants and relied increasingly on subcontracted labor. As denounced by the Union, such practices are in violation of current law. By September 2003, Coca-Cola FEMSA had closed production lines at 11 of its 16 bottling plants.

Meanwhile, workforce restructuring has slashed the ranks of Coca-Cola workers. From 1992 to 2002, some 6,700 Coca-Cola workers in Colombia lost their jobs. Eighty-eight percent of the company's workers are now temporary workers and not part of the union. Wages have been reduced by 35% for those temp workers in the last decade, and they make one-fourth what union workers earn. Temp workers have no job security, no health insurance, and no right to organize.

The company has continually pressured workers to resign their union membership and their contractual guarantees. Since September 2003, they have pressured over 500 workers to give up their union contracts in exchange for a lump-sum payment. In Barranquilla, the delegation also heard testimony from three Coke workers who said they had been fired for attending union meetings. Two of them said that they and their families are now hungry and do not have enough to cover the necessities of life.

Most of the union leaders at Coca-Cola have resisted this pressure and refused to resign. Since the delegation's return from Colombia, the company has turned up the pressure on these leaders, successfully petitioning the Colombian Ministry of Social Protection for authorization to dismiss 91 workers, 70% of whom are union leaders. SINALTRAINAL has called this "Coca-Cola's effort to essentially eliminate the union."

In response, SINALTRAINAL began a 12-day hunger strike on March 15th in eight Colombian cities to protest 11 plant closings last year. These closings resulted in the forced resignation of 500 workers, despite Colombian law and a union contract that guarantee the right to transfer from one plant to another. Two hunger strikers were hospitalized before Femsa, a Coca-Cola subsidiary, agreed to negotiate with union leaders. Negotiations are scheduled to begin on the same day this report is released, April 2nd.

Extra-legal violence

The destruction of the union, and with it the ability to slash wages and eliminate benefits, is also the aim of the campaign of violence and terror that has been directed at union members at Coca-Cola facilities. Overall, there have been a total of 179 major human rights violations of Coke workers, including nine murders. Although violence is carried out by paramilitary rather than company actors, the union has documented the concurrence of labor negotiations with the periods of greatest violence against workers.

The delegation heard testimony from dozens of Coke workers and family members who had either been the victims of violence and terror or who were eyewitnesses to them. The volume of this testimony was overwhelming, and the pattern that emerged was undeniable: union workers and especially union activists and leaders were targeted again and again in a systematic effort to silence the union and destroy its ability to negotiate for its members.

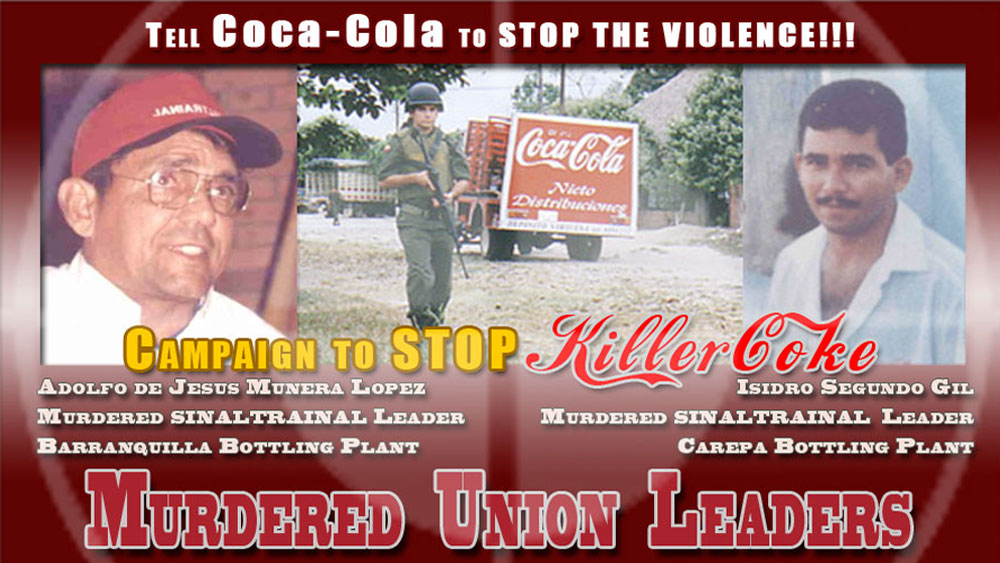

In Barranquilla, the delegation heard from the son of a Coca-Cola worker Adolfo Munera, who was assassinated in August 2002. He told the delegation:

My father was an honest, hard-working and friendly person. He began working at Coca-Cola in 1993. He joined the Coke union and began working for the rights of his co-workers. Due to that, an accusation came from the company. They [government security forces] raided the house on March 6, 1997; they came to the house, broke-in and searched the entire place. They then falsely accused my father. With the union's help, my father got a lawyer and put up a defense. At that time, the company declared my father absent from work. During that time, my father was in exile and had to move from location to location. They fired him for being absent, at which time we asked for support. Thanks to the union who gave us that support we put up a defense. Unfortunately the company handed him a letter of termination and he then went into internal exile for five years. In August 2002 he was assassinated at the door of the house of his mother.

Limberto Carranza, a Coke worker and union activist in Barranquilla, described the abduction of his 15-year old son, Jose David:

I'm speaking to the international commission as the father of a son. My son was taken September 11 of last year [2003]. A couple of hooded men took him off his bicycle as he was riding home from school. They detained him and they rode him around the city of Soledad, where we resided at the time. He was beaten; that is to say, tortured. Afterwards, he was left in a drainage ditch stunned and semi-conscious. They questioned my son about me. From the moment they started hitting him, they asked him where I was and what was I involved in. Afterwards, they told him in any case they were going to kill his father. My son was beaten...to this day...he hasn't recovered from the effects, he can't go on. He can't get over the psychological affects.

What concerns us the most is that on the 9th we had what could be called a major battle with management when the company put forth their plan to close the plants in Cartegena, Monteria and Valledupar. We organized the workers to reject the plan proposed by the company for so-called "early retirement." They played a game of intimidation by bringing the workers to different hotels in these cities, to convince them to accept the plan and abandon their job security rights in their contracts. What was the response to our organizing? The next day they kidnapped my son.

This was by no means the only incidence of violence against family members that the delegation heard about. This is perhaps the most horrifying form of terror; Cardinal Richelieu, the 17th century chief minister to Louis XIII, is said to have remarked, "a man with a family can be made to do anything." Among the other stories of threats against families was that of William Mendoza, the local president of the union in Barrancabermeja. He recounted how three men tried to kidnap his four-year old daughter on June 8, 2002, but were foiled by her mother, who held on to the child fiercely. The men then began to beat the mother, but her repeated screams attracted attention and the would-be abductors let go. After this incidence, Mendoza says a local paramilitary commander called him:

He said, "listen, you were lucky today, we were going to take your kid." He said, "we were going to kill her so that you stopped talking shit about the paramilitaries and about Coca-Cola." This is because we here in Barranca have spoken out about the paramilitarism and their probable connections with Coca-Cola. They say if I keep talking, if I don't silence myself, something will happen with a member of my family. I alerted the police to this and I haven't seen even one person detained, and the police official has not talked to me about where the case is at.... My kids go to school in the armored car to protect them. This is a very difficult situation.

It was not the last time that Mendoza's family was threatened:

The 17 of January of last year [2003] I received a call to my house to my daughter Paola. They asked her if her mother and father were there. They told her to tell them to be very careful. They asked her where she studied, she told them a certain school, and they told her she was lying, that they know that she went to a different school, and also that "right now your brother is doing chores right now in the front yard." And at that moment, my ten-year old son was actually outside in the front washing the front of the house. So they were obviously staking out our house.

The delegation talked to two survivors of the paramilitaries' campaign to destroy the union in Carepa, in the Uraba region, in 1995-1996. It was here that union leader Isidro Gil was shot seven times by paramilitary gunmen inside the Coke bottling plant. Hours later, the union's office in town was burned down. And two days after that, paramilitaries returned to the plant, lined up all the workers, presented them with prepared letters resigning their union membership, and made them sign under threat of death. The letters had been written and printed on the company's computers. The result, not at all surprising, was that the union was destroyed, and its leaders fled in fear for their lives.

Gil's murder was one of five from the Carepa plant, along with many disappearances and kidnappings. Oscar Giraldo was at the time the vice president of the local union. Before Gil was assassinated, the union's first executive board had been driven out of town and Giraldo's own brother, Vincente Enrique Giraldo, had been killed. Giraldo described the complete impunity of Gil's killers: "The police came to pick up the body and they never did any investigation. The same thing happened with my brother, they came to pick up his body and never did any, any investigation."

It was not just impunity from state prosecution that Giraldo witnessed, however. He also observed ties between the company and the paramilitaries. He told the delegation that "a supervisor told me that Mosquera [the plant's director] was going to squash us, and three days later was the assassination of Isidro Gil." Ariosto Milan Mosquera had left town shortly before the murder, right after the union had presented its bargaining demands to the company. Recalled Giraldo:

The paramilitaries could walk into the company with no problem, they would just come in and walk in, and the director kept saying that he had to get rid of the union. And he would drink with the paramilitaries and hang out with them, and everyone would tell us this. And I was told by a supervisor that the director just left to stall, and that the plan was really to get rid of the union. And I am sure that is was the paramilitaries that were told by the company to destroy the union. There was army, there was police in the town, the paramilitaries live right in the town, the police never made any attempt to stop them. And you would see the military and the paramilitary hanging out together. The paramilitaries would go around in civilian clothing with arms and they would stay in hotels. Some of them were from our own towns and some of them were from the outside. And Coca-Cola was a patron of the paramilitaries.

Attacks and threats have continued. For example, Luis Eduardo Garcia and Jose Domingo Flores, union activists from Bucaramanga whom the delegation interviewed in Barrancabermeja, told the delegation that they were victims of physical attacks on September 11, 2003. Juan Carlos Galvis, the vice president of the union in Barrancabermeja, survived as assassination attempt on August 22, 2003.

Coca-Cola inaction and complicity

Circumstantial evidence of Coca-Cola's complicity in the raw repression of its union workforce abounds. This consists in the suspicious coincidence, reported to the delegation by multiple union sources in Colombia, of waves of anti-union violence and contract negotiations between the union and the company. The union's analysis also reveals that the company's peak profits have come at times of the most intense repression.

Beyond these correlations, there are troubling eyewitness accounts of paramilitaries having unrestricted access to Coke plants and of paramilitaries consorting with company managers. When the delegation traveled to Barrancabermeja, it conducted a physical assessment of access to the bottling plant there in order to understand more precisely what paramilitary access to company property entails. The plant in Barrancabermeja is surrounded by a 10-foot high iron fence. Entry is limited to a guarded gate, which remains closed. It is simply impossible to gain access to the plant without company knowledge and permission. It is impossible to avoid the conclusion that paramilitaries in Coke's bottling plants were there with the full knowledge and/or tacit approval of the company.

The delegation also heard testimony from multiple sources that there are payments made by local Coke managers to paramilitaries. In the delegation's meeting with Coca-Cola/FEMSA representatives Juan Manuel Alvarez and Juan Carlos Dominguez on January 13, these allegations were vigorously denied. Yet, Alvarez and Dominguez acknowledged that Coke officials had never undertaken any internal or external investigations into these assertions, nor into any of the hundreds of human rights violations suffered by the company's workers.

The company's representatives also acknowledged there was a possibility that persons employed by the company-but acting without authorization-could have worked with, or have had contact with, paramilitaries. This admission makes the failure to investigate ties to the paramilitaries all the more shocking. Alvarez and Dominguez also maintained that the company assisted workers in filing complaints with the government about paramilitary harassment for union activity and promised to provide documentation thereof; to date, however, no such documentation has been received by the delegation, despite follow-up correspondence.

The January 13 exchange mirrors the delegation's experience with Coca-Cola throughout its dialogue with the company. Multiple requests for documentation have gone either unanswered or unfulfilled. Coke has shown-at best-disregard for the lives of its workers, who have been threatened, beaten, kidnapped, exiled and killed while the company has not seen fit to investigate this highly disturbing pattern affecting its workforce.

Legal reprisals

Suspicions that the company's response to the plight of its workers crosses from indifference into outright intimidation is fed by Coca-Cola's repeated resort to criminal charges against union activists.

In 1996, six union members from the Bucaramanga plant were arrested after the chief of Coca-Cola's security accused them of placing a bomb at the plant. Criminal charges were brought against three of them, and they were detained for over six months until the charges were dismissed as without merit by the prosecution. The delegation heard testimony from several of these workers, who recounted the ordeal of their unjust incarceration, sometimes under inhumane conditions, in horrid detail. The workers and their families were never compensated for damages suffered, and some report suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder incurred from their experience in prison. Coca-Cola has failed to condemn these workers' imprisonment or the false charges brought against them by their own subsidiary.

More recently, the company has brought criminal charges against some of the plaintiffs in the federal lawsuit filed in 2001 against the company in the Federal District Court for the Southern District of Florida under the Alien Claims Tort Act (ACTA). In the January 13 meeting in Bogota, Dominguez characterized these criminal charges as a "consequence" of the ACTA case, which the delegation interpreted to mean that the company intended the charges as a direct reprisal. Shortly after the delegation returned from Colombia, on January 26, 2004, the Colombian prosecutor involved in Coca-Cola's case against the workers who filed the U.S. suit dismissed the charges of slander and defamation as without merit. This represents the second time Coca-Cola's charges against its employees have been dismissed by Colombian courts. Yet Coca-Cola continues its legal strategy unabated; the company has brought similar charges against employees in Valledupar.

VI. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The delegation found both the quantity and the nature of Coca-Cola workers' allegations shocking and compelling. It seems indisputable that Coke workers have been systematically persecuted for their union activity. It seems equally evident that the company has allowed if not itself orchestrated the human rights violations of its workers, and it has benefited economically from those violations, which have severely weakened the workers' union and their bargaining power.

In the face of this evidence, Coca-Cola's continued insistence that it bears no responsibility whatsoever for the terror campaigns against its workers is highly disturbing, as is its complete failure to investigate company ties to the paramilitaries. The delegation has engaged in an earnest dialogue with the company on these issues for almost a year now, and has yet to receive any documentation backing up its denials of complicity in the situation. The delegation will continue to press for the specific documents it has been promised and to exhort the company to take urgently needed action to address the human rights crisis faced by its Colombian workforce. Specifically, the delegation reiterates its calls for:

(1) Dropping all retaliatory criminal charges against its employees. The delegation is concerned about the chilling effects of a company such as Coca-Cola filing retaliatory charges against workers who have used the legal system to address their grievances.

(2) A public statement from Coca-Cola supporting international labor rights in Colombia, denouncing anti-union violence, and initiating a long-overdue investigation of workers' allegations. The delegation believes that Coca-Cola's apparent refusal to investigate charges of such a serious nature against their employees appears to undermine their support for human and labor rights. Such a statement and investigation would serve to bolster international consumer confidence in the company's corporate behavior.

(3) An independent human rights commission. An independent human rights commission is necessary to evaluate all allegations and plant conditions to determine credible threats and identify potential means to protect both workers' rights and verify Coca-Cola's standing as a good global citizen. In order to maintain credibility and objectivity, the commission should be made up of equally participating partners from Coca-Cola, SINALTRAINAL and other relevant labor representatives and internally recognized human rights experts.

The delegation will continue its efforts to persuade Coca-Cola to take these urgently needed steps and to demonstrate that it will not tolerate profits subsidized by terror.

The delegation also urges all people of conscience to join in these efforts. We call on consumers to contact the company and add their voice to the call for corporate responsibility. We call on shareholders to exercise their power of ownership in the company. We call on churches, student organizations, community groups and civic associations to get involved. We issue a special call to unions to stand in solidarity with their brothers and sisters in Colombia being persecuted for their exercise of internationally recognized labor rights. And we call on government bodies, representing all of these constituencies, to stand up for human rights and for the ideals of American democracy, which guarantee freedom of association.

Together as stakeholders in Coca-Cola, all of us must challenge this company, the symbol of American enterprise throughout the world, to end its complicity in the persecution of Colombian workers.

ENDNOTE

1 FEMSA, the largest bottler in Latin America, owns 45.7% of its stock, while a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Coca-Cola Company owns 39.6%, and the public 14.7%. Coca-Cola/FEMSA stock is listed on the New York Stock Exchange.