Colombian Government Is Ensnared in a Paramilitary Scandal

By Simon Romero | The New York Times | January 21, 2007

Read Original

BOGOTA, Colombia, Jan. 20 — The government of President Alvaro Uribe, the largest recipient of American aid outside the Middle East, has found itself ensnared in a widening scandal as revelations surface of a secret alliance between some of the president's most prominent political supporters and paramilitary death squads.

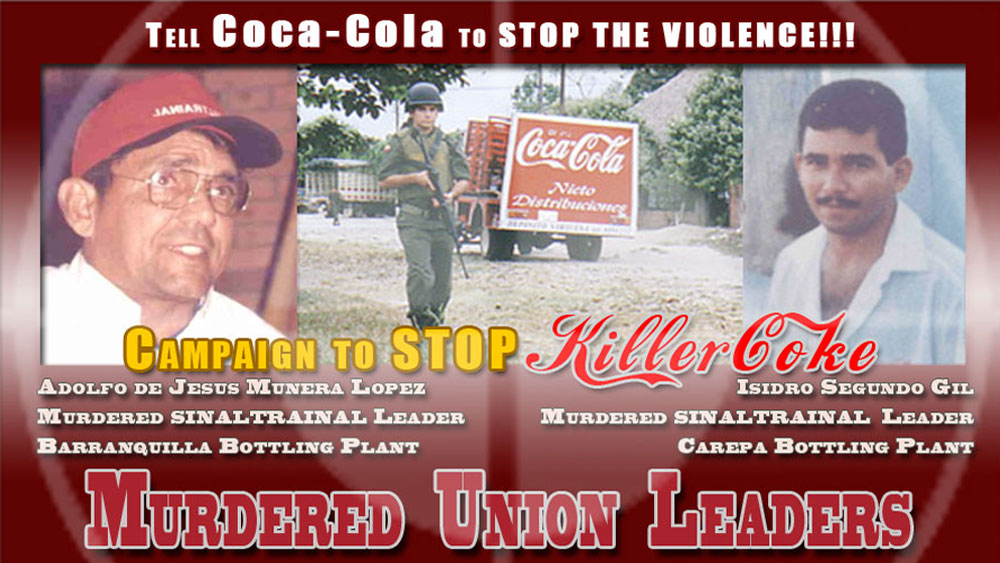

Testimony this week from Salvatore Mancuso, a former paramilitary commander who admitted to orchestrating the killing of more than 300 people, as well as a document made public on Friday implicating more than a dozen politicians in the pact with paramilitaries, have injected fresh detail into a slow-burning scandal that has caused Colombia's elite political class to shudder in recent weeks.

Pool photo by Luis Benavides

Salvatore Mancuso, center, said he oversaw assassinations, with some operations made possible with information from military intelligence.

Senior members of Mr. Uribe's government and Mr. Uribe himself have said that anyone shown to have had illegal ties to the paramilitaries, which terrorized Colombian cities and the countryside in the nation's internal war, which has gone on for decades, and made fortunes in cocaine trafficking, should be prosecuted in courts of law.

The scandal has already touched Mr. Uribe's cabinet, with Senator Alvaro Araujo, the brother of Foreign Minister Maria Consuelo Araujo, under investigation for collaborating with militias.

"If there's someone involved at the highest level, they will be fired," Francisco Santos, Colombia's vice president, said in an interview. "Scrutiny is fine for us," Mr. Santos said. "This country needs to know the whole truth."

Some of the details coming to light about the breadth of paramilitary activities are the result of a process set in motion by Mr. Uribe's own government, which has allowed paramilitary leaders to confess their crimes and pay reparations in exchange for reduced sentences of no more than eight years in prison.

Though some militia leaders have balked at the deal, much of Colombia has been gripped by the first such confession, that of Mr. Mancuso, a cattleman who helped found the paramilitary movement in the 1980s in an effort to combat leftist guerrillas.

Mr. Mancuso, 48, who studied English at the University of Pittsburgh, wept during the first days of his testimony at a special hearing in Medellin last month. This week, however, he simply read from a statement describing how he oversaw the assassinations of hundreds of people, with some operations made possible with information from military intelligence.

Mr. Mancuso also put Mr. Uribe in the spotlight by saying that militias pressured people to vote for the president in 2002, when Mr. Uribe was first elected. Mr. Uribe responded quickly by going on a national radio network to say he had never sent any emissaries to strike deals with the paramilitaries.

On the heels of Mr. Mancuso's testimony, a document rumored to exist in recent weeks was published in the daily newspaper El Tiempo on Friday. It describes a secret pact in 2001 between Mr. Mancuso, other paramilitary leaders and 11 congressmen, two governors and five mayors, in which those present agreed to work together to forge "a new social contract," largely in order to protect private property rights.

Senator Miguel de la Espriella, one of the signatories to the pact, helped bring the scandal to light last year by disclosing the ties between politicians and paramilitaries. Like other officials implicated in the pact, he said he was forced to sign, raising doubts as what type of legal punishment, if any, they might receive.

"At first we declined to sign, but when they put a man with a rifle next to the document we understood we had no choice," Mr. de la Espriella, a member of the Democratic Colombia party, said in an e-mail interview.

Asked why he was the only politician to come forward with details of the secret agreement, Mr. de la Espriella, alluding to widespread suspicions that legislators and government officials had for years worked in tandem with the paramilitaries, responded, "I told myself that a half-truth doesn't serve anybody, and we should all contribute to the enlightenment of the truth during so many years of war."

Those who signed the document included not only supporters of Mr. Uribe but also high-ranking officials in the political opposition, pointing to how a growing portion of the political establishment could be tarnished by the scandal.

Some 30,000 paramilitary members have been demobilized during Mr. Uribe's government in recent years. Colombia's military still receives more than $700 million a year in aid from the United States to combat drug trafficking and armed insurgencies.

Two guerrilla groups, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia and the National Liberation Army, still operate in the country. A truck carrying more than 600 pounds of explosives this week destroyed a dairy plant in southern Colombia owned by Nestle, the Swiss food company, an act that the police attributed to the rebels.

Although the scandal has emerged as the most pressing political challenge to Mr. Uribe's presidency, his approval ratings remain high, at above 60 percent, after five years of rule and a re-election victory last year. Many Colombians credit Mr. Uribe for declining levels of murders and kidnappings and robust economic growth.

However, political analysts here say a steady stream of disclosures related to the paramilitary scandal could diminish Mr. Uribe's credibility, particularly if implicated officials are perceived to have close ties to the president. The scandal has already entangled a former ambassador to Chile and a former head of the intelligence service.

Equally pressing for Mr. Uribe's government could be the scandal's influence on discussions in the United States Congress of aid to Colombia and a trade agreement awaiting Congressional approval that has been signed by Mr. Uribe and President Bush. Political analysts say the Democratic-led Congress is expected to add greater scrutiny of human rights issues in Colombia.

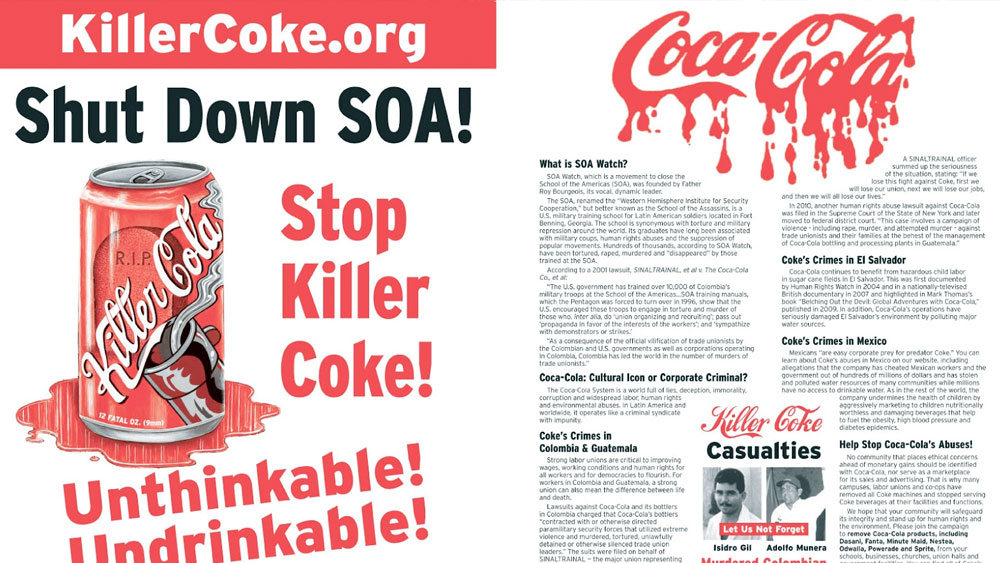

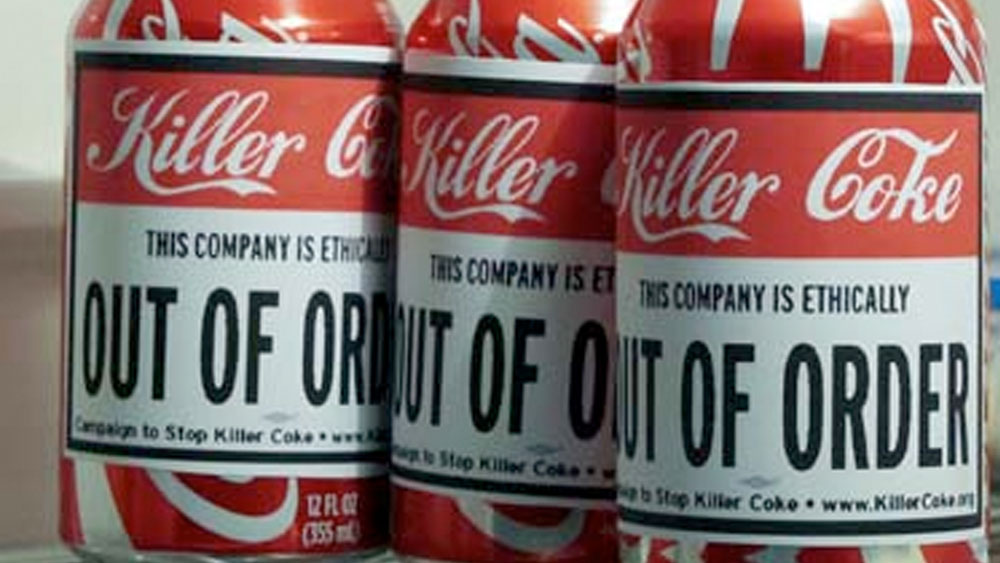

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.