Soft Drinks, Hard Feelings

Widespread student protests about alleged practices of Coca-Cola overseas prompt some colleges to rethink deals

By Anne K. Walters | The Chronicle of Higher Education | 4/14/06

Read Original

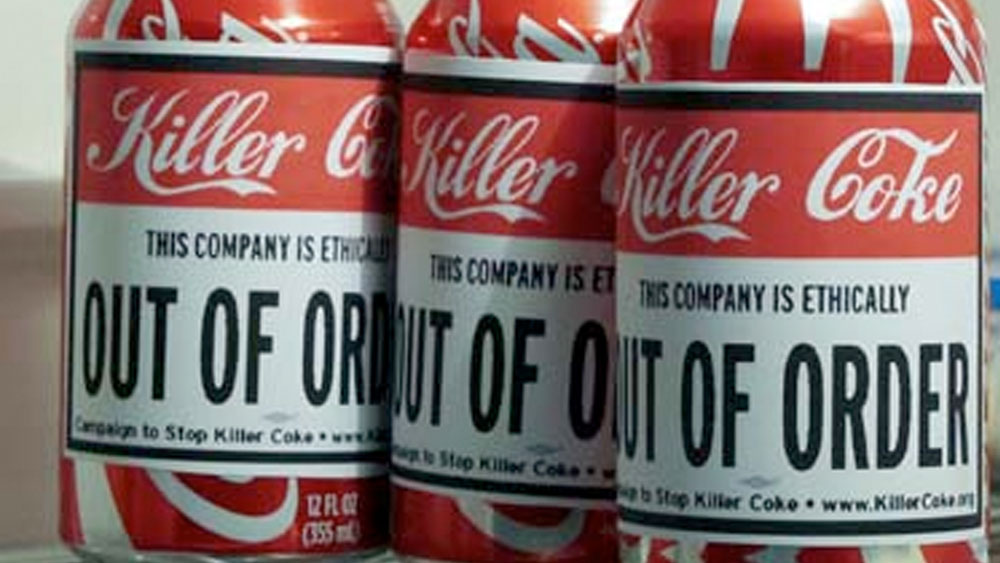

East Lansing, Mich. — About 70 students march in a circle in front of Michigan State University's administration building. Some wear red T-shirts that say "Killer Coke"; others have painted those words — or "Diet Killer Coke" — on soda-can costumes made out of garbage cans. They beat drums, wave signs that look like tombstones, and chant "Kick Coke off campus!" and "Diet, cherry, or vanilla, Coca-Cola is a killer!"

The protest in February was part of a movement at colleges across the country to get Coca-Cola kicked off the campuses.

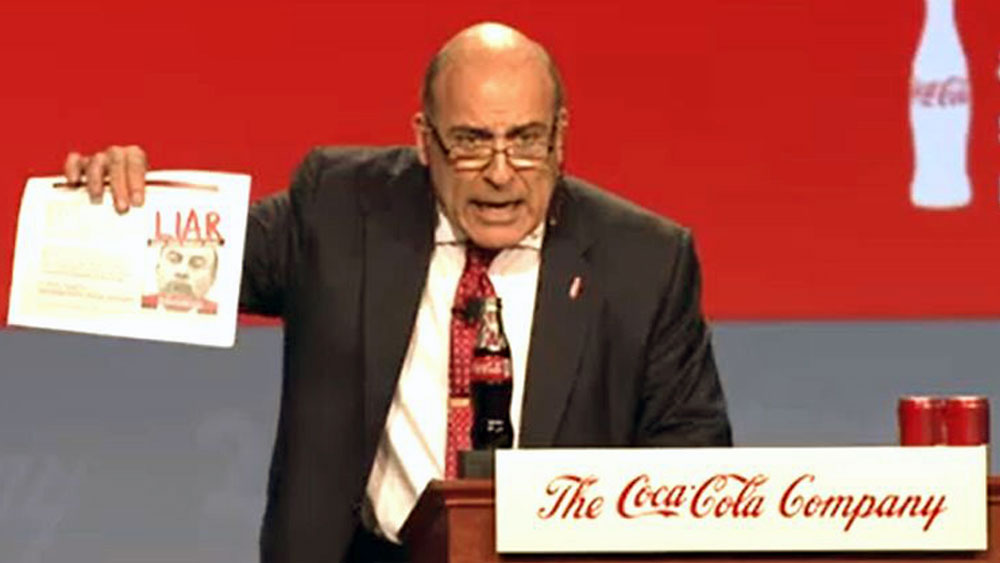

Led by the prominent labor-union activist Ray Rogers, the national campaign urges students to demonstrate against the Coca-Cola Company and boycott its products because of alleged labor abuses at bottling plants in Colombia. Coke is also accused of damaging the environment in India by polluting and draining away badly needed groundwater.

The company denies all of those accusations. But four months after student protests at University of Michigan at Ann Arbor and New York University led administrators there to stop selling Coca-Cola products, the movement has picked up steam. Student protests against Coke have erupted at DePaul, Harvard, and Portland State Universities, Swarthmore College, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Indiana University at Bloomington, and the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities, among other colleges.

Indeed, the decisions by Michigan and NYU to stop selling Coca-Cola products drew widespread attention to the campaign and gave students elsewhere renewed hope that their efforts would have an impact.

In February, Swarthmore decided to stop selling Coca-Cola products at some of its snack bars. Officials of Macalester College are considering a similar decision, despite national efforts by Coca-Cola to prevent the the boycott from spreading.

"Whether or not they like it, there's going to be a fierce protest," says Shivali Tukedo, a graduate student who is involved in the protests at Illinois.

The Allegations

Coke executives initially thought they could combat the accusations by simply mounting a defense in a lawsuit brought by a Colombian labor union and its counterparts in the United States against the company and several of its bottlers. It did not expect, and was not prepared for, the scope of the campaign being waged against it in the court of public opinion, says Pablo Largarcha, a Coca-Cola spokesman. (The parent company was later dismissed from the lawsuit, but some Colombian bottlers remain defendants.)

Now Coca-Cola representatives are visiting college officials around the country to present their own side of the story, and are arranging for an independent assessment of the company's labor practices.

The company has created a Web site, CokeFacts.org, to present its argument and to respond to Mr. Rogers's site, KillerCoke.org. A company-financed investigation of its bottling operations in Colombia last year wasn't enough to placate protesters, so it recently asked the United Nations' International Labor Organization to look into those allegations. The labor organization agreed late last month to conduct the investigation.

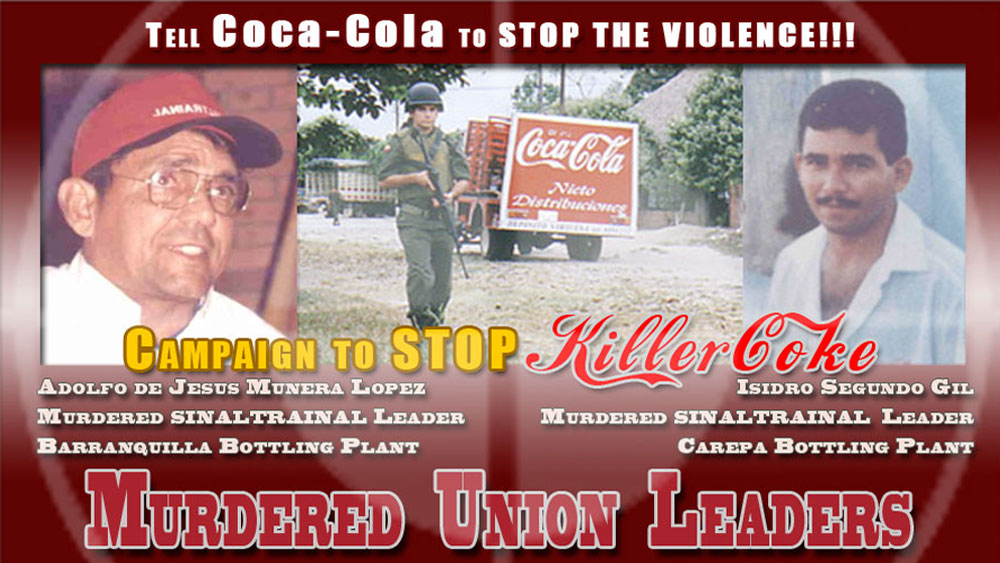

The accusations against Coca-Cola began with the mid-1990s killings of several members of the Colombian trade union, Sinaltrainal, apparently by paramilitary groups known for their anti-union violence. The groups also attacked and intimidated other union members, allegedly forcing many of them at one bottling plant to quit the union by signing prewritten statements of resignation on Coca-Cola letterhead.

Some members of the union say they saw the paramilitary troops openly communicating with Coca-Cola plant managers, and believe that the managers were involved in the violence. Although Coca-Cola bottling plants worldwide are operated by independent businesses, the parent company still has a large say in how the plants are run, and so activists blame Coca-Cola as well. The company denies that it or its bottlers were involved in the killings. The list of complaints against the company has since been expanded to include environmental problems stemming from its activities in India and accusations of union-busting in Turkey and Indonesia.

Leaders of the national campaign against Coca-Cola, along with lawyers representing the Colombian union, have dismissed the company's responses, including its request for an investigation by the U.N. group, as foot-dragging and public-relations ploys. Because one of Coca-Cola's vice presidents serves on the International Labor Organization's board, such an investigation will not be independent, they charge.

Coca-Cola says the ILO's record in setting the standard for basic labor rights should make it the "highest authority" for such an assessment.

But at this point, anything the company does will be seen as a "reactive" response to the protests, says Kellie McElhaney, executive director of the Center for Responsible Business at the University of California at Berkeley.

"Any company that's doing business on a college campus should be very aware of its social and environmental impact and should be building that into its core brand attributes," she says.

An earlier coalition between Coca-Cola and several colleges to investigate the labor complaints fell apart when the member colleges voted to expel the company.

Coca-Cola says it is trying to reach out to what it says is the majority of students and administrators who have not yet made up their minds — or who, they say pointedly, are too focused on their education to get involved with the protests.

Cola Nation

Colleges could be put in a tough spot by the campaign and the allegations of misdeeds, both financially and ethically.

Some students are pushing for colleges to establish vendor codes of conduct that set moral guidelines for companies with which the institutions do business. The activists want to duplicate the success of the student movement against apartheid in the 1980s, which persuaded colleges to divest their holdings in companies doing business in South Africa. They also see a model in recent efforts to get colleges to pressure clothing manufacturers, like Nike, to stop using sweatshops.

As young consumers, college students can exert tremendous influence on businesses like Coca-Cola, says Ms. McElhaney, of the Center for Responsible Business. "The protests that tend to be most successful are those that are launched against very well recognized global brands," she says. "That's why Coke's in a dangerous position."

The company estimates that college campuses account for 1 percent to 3 percent — $67-million to $200-million — of its $6.7-billion in sales in North America. (Pepsi-Cola, which is not a target of protests in the United States, declines to say how much business it does at colleges.)

Contracts with beverage providers amount to big money on campuses that serve drinks exclusively from one company. The money comes from the income that colleges earn selling the products, and from the bonuses that the companies pay for exclusive "pouring rights" on the campuses. Coca-Cola has a 10-year, $28-million contract with the University of Minnesota, including grants for academic, campus life, and community programs.

Coca-Cola's reach is felt strongly in college sports. It has a $500-million contract with the National Collegiate Athletic Association ensuring the company advertising and sponsorship rights.

In addition to reaping profits from selling drinks to students, Coca-Cola hopes to win them as lifelong customers. "It's very important, and we as a company have always tried to establish emotional bonds with the younger population," says Mr. Largarcha, the Coca-Cola spokesman. "Not just what the brand communicates, but what the company is."

Aware of that strategy, anti-Coke activists want to strike the company where it hurts. "When you get them banned," says Mr. Rogers, "they lose what they really look to do, which is brand students." His organization, the Campaign to Stop Killer Coke, helps student activists around the country by printing anti-Coke fliers and providing groups with suggestions for getting Coke kicked off their campuses. His Web site provides a campus-activism guide from United Students Against Sweatshops, an advocacy group, that details allegations against the company, tells students how to locate their college's beverage contract, and gives tips for holding demonstrations and getting other student groups involved.

Fizzy Business

Stepping into one of the many dining halls that serve the 44,000-plus students here at Michigan State, visitors are greeted by rows of glowing red vending machines that dispense Coca-Cola products, which also include Sprite, Nestea, and Minute Maid juices. No machines from other companies are in sight.

With so much Coke, some students who saw the demonstration outside the administration building here wondered how effective the protest could be against a multinational corporation, and whether the effort was worthwhile. "You don't want anyone to be suppressed," says James Parrelly, a junior who paused to look at the protests between classes. "But I also think that there are greater problems."

The campaign has gained momentum abroad as well, but not always with as much success as organizers would hope. A Coke boycott was voted down last month by the membership of the National Union of Students, in Great Britain.

Meanwhile, on a few American campuses, some students do their best to promote Coke products. At the University of Montana at Missoula, the student government passed a resolution supporting the university's contract with Coke. At Michigan State, the anti-Coke protest drew counter protesters from Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative group. They sipped cans of the soft drink and handed passers-by literature drawn from the company's site.

Michigan State does not have a contract that limits on-campus sales only to Coca-Cola products, and there are several soft-drink options in campus stores, but many students object to Coke's exclusivity in the dining halls.

"Essentially, everyone who pays for a meal plan pays for Coke whether they support it or not," says Tommy Simon, a junior who belongs to Students for Economic Justice, which held the February protest. The group, affiliated with United Students Against Sweatshops, hopes to persuade the university to sever its ties with Coca-Cola by the end of the semester.

That seems unlikely to happen. Michigan State is in the middle of a decade-long contract with Coca-Cola. And with the largest university-run food service in the country, the institution goes through 60,000 gallons of Coke's patented syrup in its drink machines each year, says Charles M. Gagliano, assistant vice president for housing and food services. University officials chose Coke for the dining halls because the company offered the best prices for the fountain drinks, even without exclusive pouring rights. Students can buy Pepsi products in campus vending machines and a variety of beverages in bottles at campus stores.

Still, Mr. Gagliano and other administrators sat down with members of Students for Economic Justice to discuss Michigan State's contract with Coke last month, and both parties describe the meeting as friendly and productive. Administrators say they need more-conclusive evidence of wrongdoing by Coca-Cola before they would consider choosing a different soft-drink provider.

The university "will rely on third-party investigators or the U.S. courts," says Mr. Gagliano.

Getting the Word Out

Members of the activist group at Michigan State hoped to provide such evidence against the company when they brought Luis Cardona, a former employee of the Coca-Cola bottling plant in Colombia, to speak on the campus in February. They were disappointed that no administrators attended the event.

Mr. Cardona has traveled to dozens of campuses with Camilo Romero, a national organizer with United Students Against Sweatshops, telling tales of threats by Colombian paramilitary groups and accusing managers of the Coca-Cola bottling plant of involvement in the intimidation and in the killings of several of his fellow union members.

"With every Coke product we consume, we are complicit with violence in my country," he told a group of about 100 people in a meeting room of the Michigan State Union. He has been taking his message to campuses because, he says, "students have the capacity and energy to change policies."

The crowd seemed largely receptive to what Mr. Cardona had to say as Mr. Romero translated his words from Spanish to English. Despite the language barrier, the two men managed to whip the students into an anti-Coke cheer, repeated in halting Spanish, at the end of the evening.

Students for Economic Justice has continued to hold events on Michigan State's campus each week to spread its message.

Although students who are not in the group have not complained about Coca-Cola products to Mr. Gagliano, the company was concerned enough to contact administrators and take out a full-page ad in the student newspaper explaining its side of the story.

Administrators here have said they are waiting for the results of an independent investigation of the company, and some universities, including Michigan, say they might resume purchasing Coke products if an investigation clears its name. No timeline has been set for an independent investigation by the International Labor Organization.

But as members of Students for Economic Justice gather for a meeting after Mr. Cardona's speech at Michigan State, they make it clear that they plan to stick with their campaign until they get Coke kicked off their campus. Last month, as part of a protest, the group served beer from the Michigan Brewing Company outside the administration building. The event was dubbed "Take a (Keg) Stand Against Coca-Cola."

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.