'Killer Coke' — Campaign Grows Against the Cola Giant

By Ian Werkheiser | Z Magazine Online | July/August 2004 Volume 17 Number 7/8

Ray Rogers isn't afraid to speak highly about his own projects. "Frankly, I've seen organizations and unions spend millions and millions of dollars and what they accomplish can't begin to compare with what we've already accomplished." Rogers is the head of the Campaign to Stop Killer Coke and Corporate Campaign Inc. (CCI).

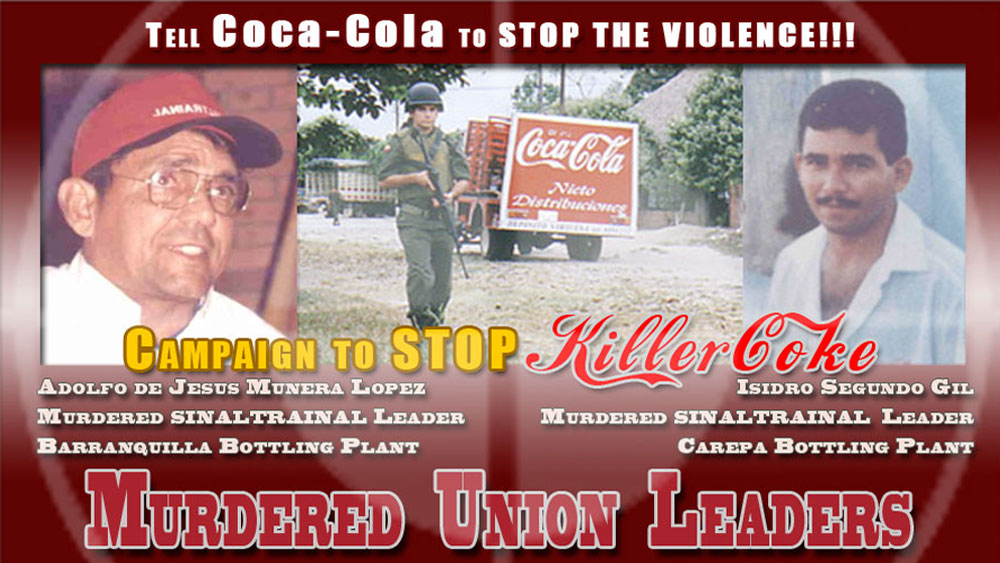

The International Labor Rights Fund and United Steelworkers of America filed suit against Coca-Cola in 2001 on behalf of SINALTRAINAL, a union in Colombia which had been the target of attacks by paramilitary forces. The case was also brought on behalf of some of the organizers who had been targeted and the estate of one of the murdered members of SINALTRAINAL, Isidro Gil. The suit contended that this was done on behalf of the bottlers in Colombia, and Coca-Cola more specifically. In the same year that many of these abuses took place, Coca-Cola made over $4 billion in profit and CEO Douglas Daft received $105 million in compensation.

Coca-Cola scored a victory by initially getting the suit thrown out, though this decision is being appealed. Thereafter it was decided that a more cohesive public campaign would be needed to supplement the legal strategy; that is where CCI came in. After conducting months of research into the company, CCI came up with a four-part plan: challenge Coca-Cola's reputation, attack their markets, target specific shareholders, and target specific investors. This strategy seeks to divide the decision makers against themselves. As Rogers says, "It's just being able to raise the stakes high enough that it's going to cost Coke a lot more than they have to gain if they don't clean up the situation."

Public Relations

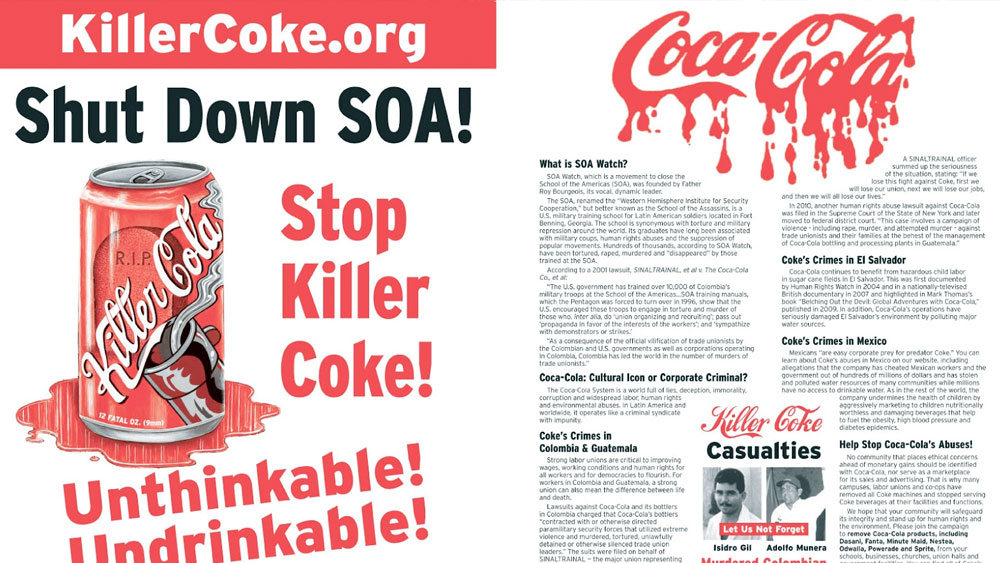

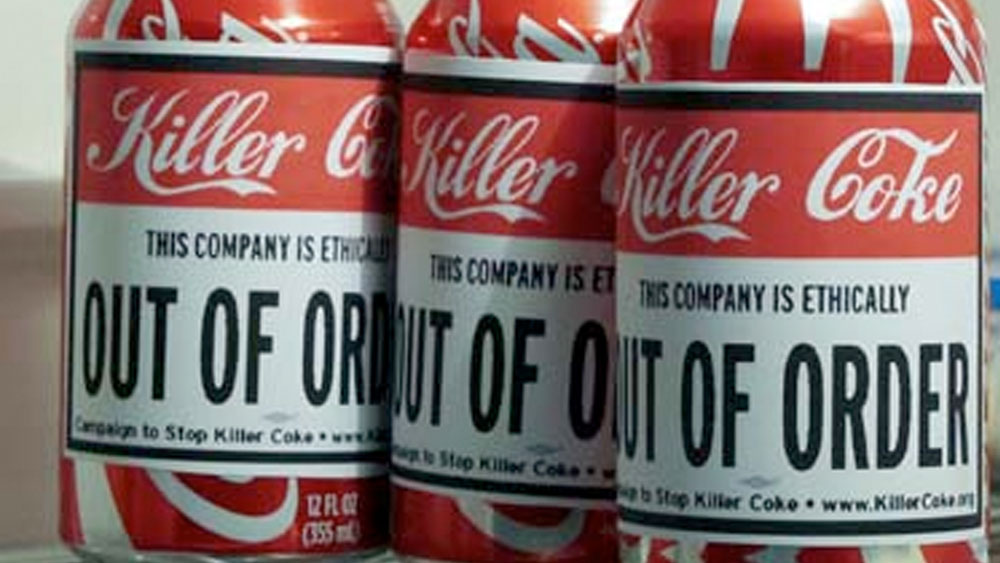

The first part of Rogers's plan is public relations. Their aim, he says, is "to mount a threat to the image and reputation that Coke has spent billions of dollars and decades to create" — an image clearly important to a company that spends over $1 million a day on U.S. advertising alone. Campaign to Stop Killer Coke has produced hundreds of thousands of posters, stickers, and pamphlets, with professional looking graphics and strong messages. One poster shows an open coffin with the heading "Murder — It's the Real Thing." These pamphlets are distributed at protests and Coca-Cola meetings. A small idea that had large results.

On October 23, 2003, Deval L. Patrick, executive vice president, general counsel, and secretary for the Coca-Cola Company was to receive an award from Equal Justice Works, a public interest law group. In attendance were Janet Reno, Alexis Herman, and others. Campaign to Stop Killer Coke stood outside the Washington, DC Marriot handing out flyers mentioning Coca-Cola's abuses and specifically targeting Patrick. At the ceremony, the public interest and pro-bono advocating attorneys asked Patrick about the claims, at which time he publicly stated that there would be an independent investigation into the matter.

As the Washington Post reported on April 22, though initially claiming to be supportive of an investigation, CEO Douglas Daft later quashed it. This was a significant contributing factor in Patrick's resignation on Easter Sunday 2004 (Washington Post, April 22, 2004). This kind of pressure is very damaging to Coca-Cola and is the sort of grass-roots activism that can fight back against Coke's slick PR.

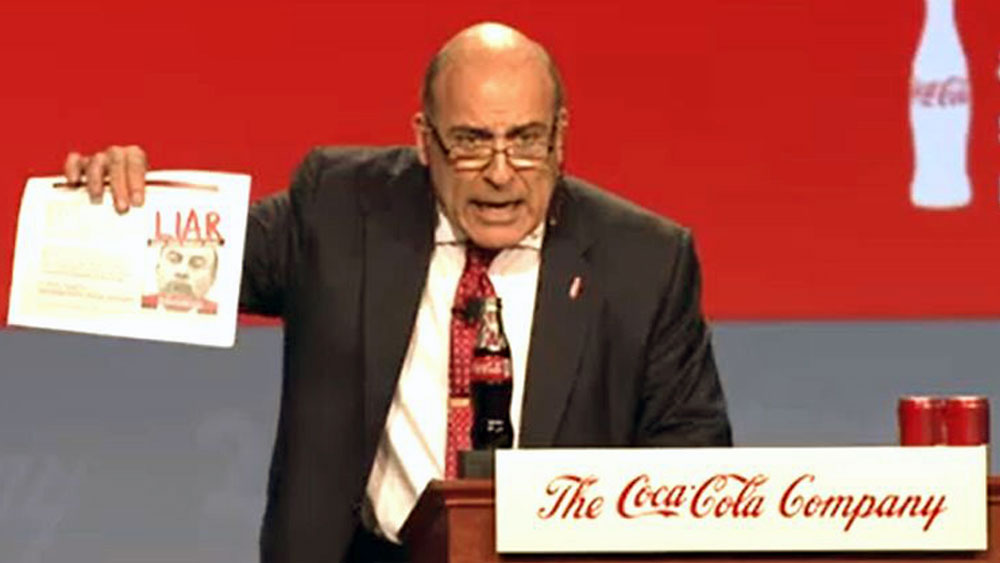

This pressure also took the form of Rogers speaking as a proxy for 3,000 shares at the last Coca-Cola shareholder's meeting. Rogers took Coke to task for everything from the abuses in Colombia, and other places in the world, to the striking Teamsters outside the building, asking "Where does the greed stop?" Rogers was assaulted by six security guards, at least one of whom turned out to be a Wilmington police officer, though the Wilmington police have not commented as to whether he was on city time or a hired agent of Coke. The CEO was heard saying, "We made a mistake," and, indeed, they may well have. (Rogers was not arrested and is currently looking into filing assault charges against the company.) This also prompted a spate of articles, further getting out the message.

The public relations story for Coca-Cola gets worse. New York City Councilperson Hiram Monserrate, whose district includes many Colombian Americans, led a delegation to Colombia to investigate the claims against Coca-Cola. The report is a stinging condemnation. As it says, "Most troubling to the delegation were the persistent allegations that paramilitary violence against workers was done with the knowledge of and likely under the direction of company managers. The physical access that paramilitaries have had to Coca-Cola bottling plants is impossible without company knowledge and/or tacit approval. Shockingly, company officials admitted to the delegation that they had never investigated the ties between plant managers and paramilitaries. The company¹s inaction and its ongoing refusal to take any responsibility for the human rights crisis faced by its workforce in Colombia demonstrates — at best — disregard for the lives of its workers." Monserrate will also be holding public hearings into this case in September.

Attacking Markets

Though SINALTRAINAL was calling for a general boycott of all Coke products, Campaign to Stop Killer Coke took a different tack. Rogers doesn't want, he says, "some reporter saying to me every month or two or three 'Your campaign isn't working, they're selling more coke.'" A boycott is hard to do to so ubiquitous a company, especially when many of their products don't contain the words "Coca-Cola" on them. Additionally there is the problem of calling for a boycott on a company that has some union workers, notably some of the delivery drivers and bottlers. Instead, Campaign to Stop Killer Coke has targeted exclusive distribution contracts, which allow Coca-Cola to be the only product at an institution.

Some of their biggest successes to date have been with universities. Three colleges in the U.S., and more internationally, have cancelled their contracts with Coke. When Carleton College, a small school of 2,000 students in Minnesota, held hearings on whether or not to renew their contracts, five representatives from Coca-Cola, including two executives, came to try to convince the students in charge of the contract to renew. Campaign to Stop Killer Coke, in alliance with students, also showed up to debate them. Their contract was not renewed. There are also battles for upcoming contract renewals at Rutgers University and the University of Massachusetts, where Campaign to Stop Killer Coke sent 5,000 emails to every administrator, professor, and staff member on campus.

Many unions and labor councils have also stopped using Coke products, including the ILWU, UAW's biggest GM local in Detroit, and labor councils in Vancouver and Ontario. But the big fight in the future, the campaign claims, will be with government contracts. There is an upcoming contract to supply soft drinks to all government buildings in New York, which could mean hundreds of millions of dollars. Coinciding with councilperson Monserrate's hearings into Coca- Cola's connection to these abuses, Campaign to Stop Killer Coke will be working to keep Coke from getting the contract. Rogers even has other corporations do some of the work for him in the form of Coke¹s competitors. As he says, "We¹re reaching out to any and all of Coca-Cola's competitors, saying to them, 'This is where we're going after Coke. You get in there and take your best shot. Take their market.'" This will be especially effective in the New York government contract, where Pepsi and Snapple are also vying for distribution rights.

Targeting Investors

Some of the most effective weapons in Rogers's arsenal are his attacks against decision makers in the company, rather than the company as a faceless entity. Rogers explains: "You have to personalize your campaign. Bricks, mortar, and machinery don¹t make decisions that seriously hurt workers and communities. People do. That's why you always have to personalize a campaign. You have to find out who really has the power or can influence the decision to resolve this situation. So we analyze the company, look at its board, look at top officers. They have to be held responsible and you have to take the fight to their doorsteps and into their boardroom."

In Rogers's sights — Suntrust Banks and Warren Buffet. Campaign to Stop Killer Coke and other union and labor groups are calling for a boycott of and disinvestment in Suntrust Banks. Their relationship with Coca-Cola is described by Rogers: "I've studied corporate structure for years, this is the most incestuous relationship I've ever seen." Suntrust took Coke public in 1919, and there are six "interlocks" of present and former CEO's sitting on each other's boards of directors; even on Coke-FEMSA and Panamco (the bottling companies also named in the suit). Warren Buffet, the billionaire who was on Governor Schwarzenegger's campaign as an advisor and is now advising presidential hopeful John Kerry, is the largest holder of Coca-Cola stock and is the fifth largest stockholder in Suntrust Banks.

Fortune magazine describes Coca-Cola's leadership as "Coca-Cola keiretsu because it so resembles the web of interlocking relationships typical of corporate boards in Japan" (though they hasten to point out that this isn't illegal). Rogers believes that these connected groups and individuals are much more vulnerable than the company. While Buffet may react to negative publicity, an institution with fiduciary responsibility to its investors like a bank is especially vulnerable. "I maintain that if there's enough pressure put on Suntrust, that this situation in Colombia will be resolved very quickly."

A Winnable Fight

Coca-Cola claims that they do not own the bottling companies in Colombia, so that even were those companies committing crimes, there would be nothing Coke could do about it. But history disagrees.

In the 1980s in Guatemala, many organizers trying to unionize workers at Coca-Cola bottling plants were killed. Due to intense international pressure, Coca-Cola, which didn't own those bottling companies either, threatened to pull out as their client and the situation changed immediately. In addition to being the major client of the plants in Colombia, Coke and its subsidiaries own nearly 50 percent of the stock of the bottling companies and all of the series "C" preferred stock — meaning they have veto power over any mergers or major changes.

Rogers doesn't doubt that Coke will eventually buckle to the bad publicity, but is concerned over the time frame. "We need a lot of help in volunteers. More money means getting this resolved more quickly." While they say they can use help, it is an object lesson what a staff of only a handful on no budget can accomplish.

Rogers is certainly confident about his tactics and organization. As he says, "I've had very big players in the corporate world try to get me to work for them. I wish some of the top union leaders treated me the way union busters do. But, unfortunately, that's one of the big problems within the labor movement. There's not a lot of real commitment or a real analysis of how you take on the corporate and political structure. There's a lot of good people who can do a lot of good stuff but they don't really get it."

In 1994, with the Republicans in control of Congress, Representative Peter Hoekstra (R-MI) pushed for "corrective legislation" targeting the kind of campaign CCI advocates and calling for a full committee investigation. This was dropped rather unceremoniously over free speech objections. But it's clear that corporate-style campaigning has major corporations worried.

Ian Werkheiser is a teacher and freelance writer living in Japan.

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.