Coke's World of Woes

New Coca-Cola CEO E. Neville Isdell faces declining U.S. market share, an antitrust investigation in Europe, labor unrest in Colombia and environmental charges in India.

By Adam Levy and Steve Matthews | Bloomberg Markets | July 2004

Coca-Cola Co. Chief Financial Officer Gary Fayard wrapped up an early-morning analyst conference call on April 21 after the world's biggest beverage company had posted a 35 percent first-quarter profit increase, its biggest gain in a year. Then he ducked outside for a quick smoke in front of the Hotel du Pont in downtown Wilmington, Delaware. "Just got off the analyst call, and it went great," Fayard told Herbert Allen Jr., Coca-Cola director and chief executive officer of New York investment firm Allen & Co., who was walking into the hotel's Gold Ballroom for Coca-Cola's annual shareholder meeting.

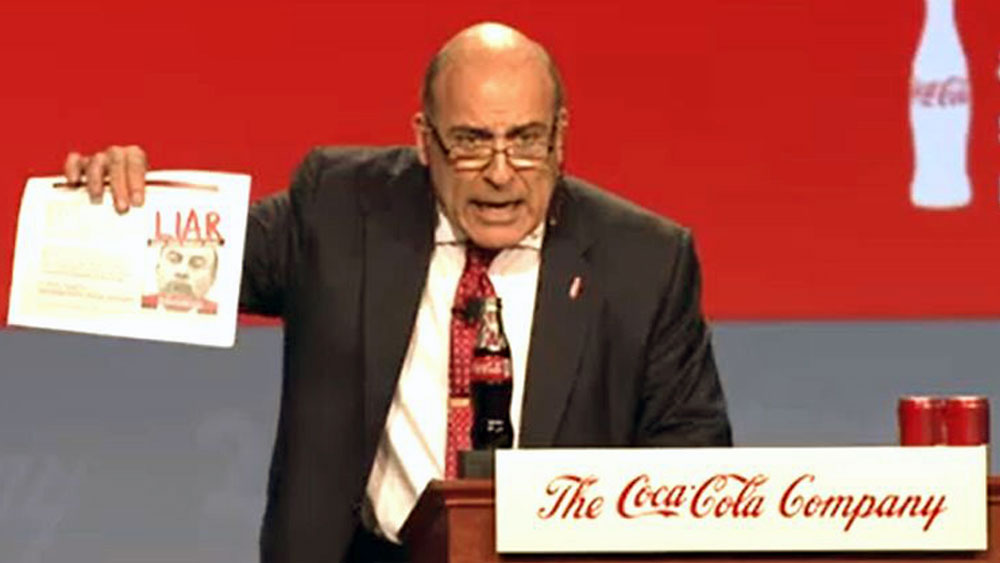

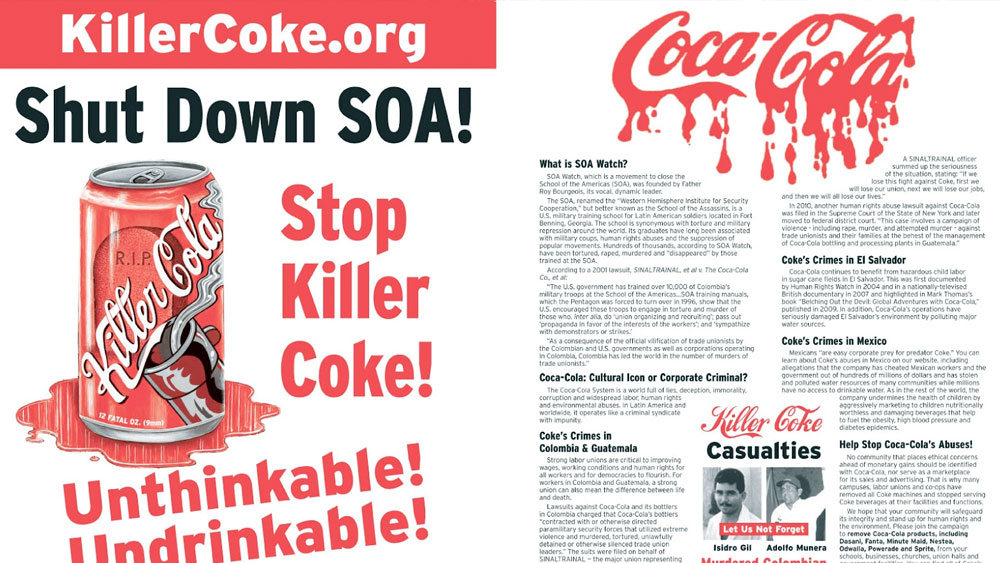

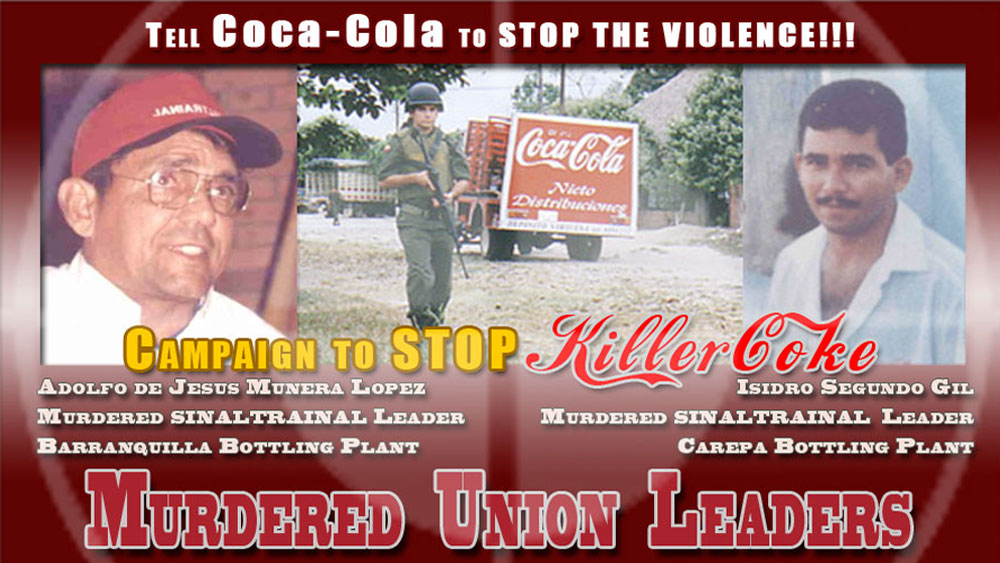

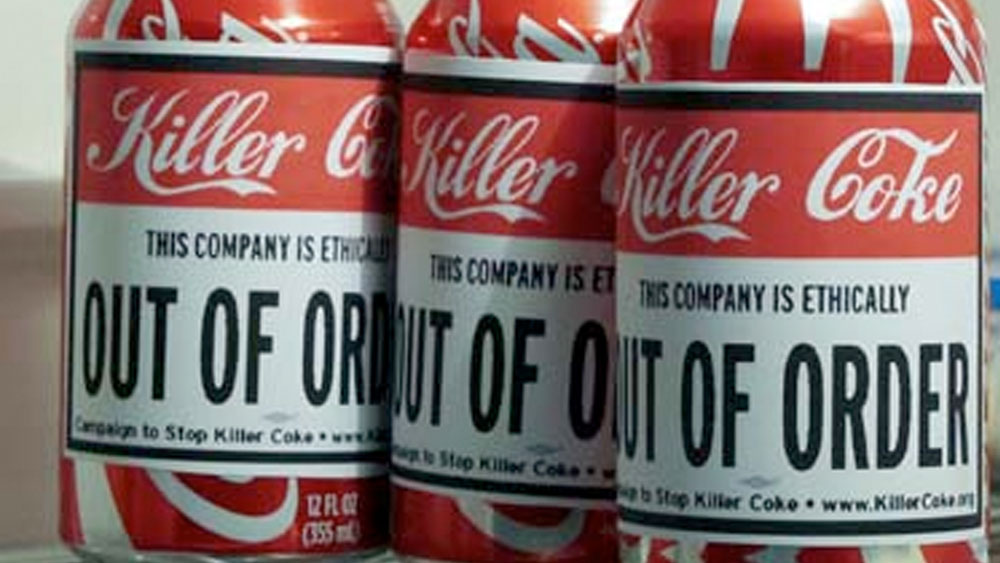

That was the high point of the day for Coke executives. At the meeting an hour later, Ray Rogers, a director of New York-based shareholder activist group Corporate Campaign Inc., began protesting Coke's alleged complicity in fomenting antiunion violence in Colombia and wasting water in India. When he wouldn't leave the microphone after his two-minute time allotment expired, security guards wrestled him to the floor. Coca-Cola Chairman and CEO Douglas Daft, 61, tried in vain to restore order. "Please stand down; please be gentle," he urged security guards.

The fracas was a suitable reminder of the current state of affairs at the Atlanta-based company. Four years after Allen, Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Chairman Warren Buffett and the other 10 directors of Coca-Cola replaced Douglas Ivester with Daft, the company is in turmoil. "They are mired in issues," says Allen Adler, president of New York-based Allen Adler Enterprises, who owns an undisclosed number of Coca-Cola shares. "Something always hits them out of the blue."

The blows have come at a steady pace, and it will now fall to new CEO E. Neville Isdell, who was appointed on May 4, to fend them off. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and prosecutors at the U.S. Attorney's Office in Atlanta are investigating former employees' charges, according to company filings. Those charges include claims that Coke inflated profit by shipping excessive amounts of soft-drink syrup to bottlers in Japan and North America-a tactic called channel stuffing-according to company filings. The European Commission is investigating Coca-Cola for possible antitrust abuses; the company says it wants to meet with commission members to address their concerns.

In March, Coca-Cola recalled 500,000 bottles of its Dasani water in the U.K., following a lab analysis that found as much as 2.5 times the allowable level of bromate, a carcinogen. Coke shelved plans to sell Dasani in France and Germany, crimping plans to expand in the $46-billion-a-year bottled-water market-which has grown an average of 11 percent annually over the past three years, according to Paris-based food company Groupe Danone.

On March 31, at Yale University in New Haven, Daft bolted early from a reception after 20 students accused Coke of being indifferent about the murder of some Colombian employees, including a union manager killed at a local bottling plant. The students lay on the floor as if they were dead during Daft's speech about the ethical and moral responsibilities of businesses. "Charges linking our company to these atrocities are false and outrageous," Daft said at the annual meeting.

In India, a parliamentary panel in February upheld a report by a New Delhi-based research institute that said Coca-Cola's drinks contained pesticide residue. The southern Indian state government of Kerala has banned the company from using groundwater extracted locally for its plant in Plachimada because of protests that it was depleting the resource. A Coke spokesman says the company complies with all relevant standards.

Back at Coke headquarters in Atlanta, there has been frequent turnover in the executive suite. Since Daft was appointed CEO in February 2000, several of his top lieutenants have bolted: President Jack Stahl, who now heads Revlon Inc., quit in March 2001; Jeff Dunn, who ran North American operations, resigned in December 2003; Tom Moore, president of the soda fountain business, left in August 2003; Stephen Jones, top marketing officer, quit in March 2003. In mid-April, General Counsel Deval Patrick, 47, the company's top-ranked black employee and a former U.S. Justice Department civil rights chief under President Bill Clinton, announced his departure.

In February, Daft surprised analysts and investors by announcing 2004 would be his final year at Coca-Cola. At a company once known for its deep management bench-just five years ago, Coke's top seven executives had a total of 173 years of beverage industry experience-no one with a long company pedigree was left. For the first time in its 118-year history, Coca-Cola looked at outside candidates for its top job. In April, three of them-Gillette Co. CEO James Kilts, Mattel Inc. CEO Robert Eckert and Kellogg Co. CEO Carlos Gutierrez-each withdrew from consideration.

Then on May 4, the board called back from retirement former Coke executive Isdell, 60, and named him chairman and CEO. He will take over in early summer. Isdell, born in Northern Ireland and raised in South Africa, joined the company in 1966 in Zambia. He ran its European unit in the early and mid 1990s and left in 1998 to run Coca-Cola Beverages Plc, one of the company's biggest bottlers. Isdell, who retired at the end of 2001, was passed over for the top job in 1997 and again in 2000.

The appointment didn't impress many of the company's critics. Robert van Brugge, an analyst at Sanford C. Bernstein & Co., says Isdell's appointment is a step in the wrong irection. "The company needs somebody to shake up the culture internally, and you're not going to do that by bringing in the old guys," van Brugge says. "A lot of investors are going to be disappointed by this choice." Douglas Lane, who manages $1.3 billion at New York-based Douglas C. Lane & Associates, including about 350,000 Coca-Cola shares, expressed disappointment. "They are going for no change rather than a lot of change," he says. "They hired another Daft."

Tom Pirko, president of Bevmark LLC, an industry consulting firm in Santa Barbara, California, says Isdell may find it hard to make changes because of brakes applied by directors such as Buffett, 73, and former Coke President Donald Keough, 77. "The company needs to move into this century," Pirko says. "It needs to take risks and come up with new products, new brands, new marketing. But this company is run by a very conservative board that made a very conservative choice in appointing Isdell."

Isdell faces an energized archrival. Purchase, New York-based PepsiCo Inc. has notched an average annual sales gain of 3.8 percent since Daft was appointed CEO in 1999-two-thirds better than Coke's 2.3 percent. PepsiCo profit rose an average of 12.4 percent during the past five years, while Coke's rose an average of only 4.2 percent.

Coca-Cola shares exploded during the 16-year tenure of former CEO Roberto Goizueta, who pulled the company out of shrimp farming and the Taylor wine business and pushed it into Columbia Pictures. Coke's market value rose to more than $150 billion from $5 billion. Since Goizueta died of lung cancer in 1997, Coke shares have declined 14 percent to $50.05 on May 11 from $58.50. By comparison, Pepsi shares have risen 42 percent during the same period to $53.78 on May 11 from $37.94.

Under Daft, Coca-Cola focused mainly on introducing new flavors of its carbonated beverages: lime- and lemon-flavored Diet Coke and Vanilla Coke. Extending drink lines instead of developing new ones takes sales from existing brands, says Morgan Stanley beverage analyst William Pecoriello. Also, the carbonated-soft-drink market has lost its fizz in the U.S.-where growth has been less than 1 percent a year over the past five years-and in other developed countries. Coca-Cola gets 83 percent of its sales from sodas. At PepsiCo, bubbly drinks account for less than half of sales. "Pepsi's been more aggressive in noncarbonated beverages, which is the fast-growing part of the business," says Gary Hemphill, senior vice president at Beverage Marketing Corp., a New York-based industry consultant. "They have the No. 1 bottled-water brand in Aquafina. They have Gatorade."

As of March 21, PepsiCo's Gatorade accounted for 82 percent of U.S. sales of sports drinks-a $3 billion annual market that grew 11 percent last year-compared with 14 percent for Coca-Cola's Powerade, according to Information Resources Inc., which tracks supermarket checkout scanners. Pepsi also outpaces Coke in the $8.3-billion-a-year U.S. bottled-water business, which is growing at a 9 percent annual pace, according to Beverage Marketing. Pepsi introduced Aquafina in 1995, and Coca-Cola responded with Dasani in 1999. Dasani sales reached $834 million last year, up more than sixfold from $130 million in 1999. The brand still lags Aquafina, which had sales of $936 million in 2003, according to Beverage Marketing.

In the soda business, Pepsi is on the move. Sierra Mist, a lemon-lime drink that competes with Coca-Cola's Sprite, almost doubled sales last year and became one of the 10 largest-selling U.S. brands, according to industry research firm Beverage Digest LLC. Pepsi's advertisements resonate more with consumers as well: The ad most remembered by consumers during 2003 was one for Pepsi Twist that featured rocker Ozzy Osbourne's nightmare in which his children are actually Donny and Marie Osmond in disguise, according to Advertising Age magazine's annual survey. Coke didn't have a commercial in that most-remembered category. "Pepsi has been more innovative than Coke," says John Thompson, who manages $2 billion at Thompson Investment Management, including 1.24 million Coke shares and 1.1 million Pepsi shares. "Their advertising is not as strong as Pepsi's, and that has hurt them. Coke hasn't executed well lately."

Overall, PepsiCo has narrowed the gap in the U.S. beverage industry to its closest margin in a decade. Pepsi's share of the $63.8 billion market climbed 0.4 percentage point to 31.8 percent in 2003; Coca-Cola's share slipped 0.3 percentage point to 44 percent. "Pepsi is firing on all cylinders," says Robert Morris, director of equity investments at Jersey City, New Jersey-based Lord Abbett & Co., which holds 13.2 million Pepsi shares.

Emanuel Goldman, 66, who has tracked the beverage industry as a Wall Street analyst for 28 years and who now runs Goldman Consulting Services in Hillsborough, California, says Coca-Cola's woes began in earnest with the end of Goizueta's reign in 1997. "Goizueta's sudden death brought about a major discontinuity," he says.

For one thing, according to Coca-Cola director and former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn, the board wasn't well prepared to name a successor at that time. "I don't think the board had done nearly as much at that stage as it has since then in terms of real leadership development and having a broad feel for the top people that are under the CEO," Nunn, 65, said in a January 2004 Harvard Business School case study about Coca-Cola's board of directors.

The board picked Ivester, then 50, a former accountant who had joined the company 18 years earlier as assistant controller, to replace Goizueta. Ivester's tenure was rocky: During a contaminated-drink outbreak in Belgium and France in the summer of 1999, he waited a week before apologizing to European consumers. Coke's slow reaction turned the event into a public relations crisis that pummeled sales and led to a $75 million product recall. Ivester also riled regulators in Europe for trying to take over Cadbury Schweppes Plc's beverage brands without getting clearance, according to Karel Van Miert, Europe's top antitrust official from 1993 to '99. In July 1999, European Union officials ordered a raid of Coke's European offices as part of an investigation into the company's dealings with retailers.

Ivester quit after 26 months at the helm of Coke, and the board picked Daft to replace him. An Australian who speaks with a broad accent, Daft taught high school before joining the company in 1969 as a planner in Sydney. He has worked in Indonesia, Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo and Atlanta, overseeing Asian and Middle Eastern markets, including Pakistan and Vietnam. In the early 1980s, Daft helped execute Coke's reentry into China. In a 2001 interview, Daft said he was learning on the job how to deal with the board. "It's not something I was trained for," he said.

Daft's first focus: cutting costs. He fired more than 5,000 workers, the company's biggest job reduction, during his first year. Last year, he eliminated 3,700 jobs, including 1,000 when Coca-Cola consolidated its three North American business units: North America, Minute Maid and Fountain divisions. "Daft wasn't supposed to be chairman," says Goldman, the former analyst. "He was never trained to be chairman, and he didn't have a year to get up to speed. The killer was when they started to fire people. If you are working at Coke, you are going to step back so you don't get fired. People weren't willing to take risks."

Daft also brought in outsiders such as Steven Heyer, 51, former president and chief operating officer of Time Warner Inc.'s Turner Broadcasting System, to revamp advertising. One result was a recent series of TV ads for Powerade, Coke's sports drink, showing National Basketball Association Rookie of the Year Lebron James sinking baskets from beyond half court.

In 2003, Daft formed an Innovation and Development team composed of 80 top marketers and researchers to work on the priority project of finding the next Vanilla Coke, whose 90 million cases sold in its debut year of 2002 ranks it among the best-selling new products in Coke's history. Daft also shored up relations with Coke's bottlers. He held back from big price increases on syrup, indirectly helping the parent company, which owns 37 percent of Coca-Cola Enterprises Inc., its largest bottler. Coca-Cola Enterprises shares have jumped 23 percent this year, following an almost 15 percent gain in 2002 and a less than 1 percent gain in 2003.

Even so, Coca-Cola stock has dropped 4 percent under Daft, as investors have faced a series of management missteps. Last June, Coke said some employees had improperly manipulated results of a market test of fountain sales at Burger King Corp. A consultant paid by Coke bought scores of meals, including chicken sandwiches and frozen Cokes, to influence a promotion at the chain's restaurants in Richmond, Virginia, in March 2000. Burger King officials said they were disappointed and that Coke's actions were unacceptable. In August, Coca-Cola settled the dispute with Burger King, agreeing to pay as much as $21.1 million in compensation, according to a letter to franchisees obtained by Bloomberg News.

Burger King scrapped plans to drop the beverage. In October, Coca-Cola agreed to pay $540,000 to settle a lawsuit by Matthew Whitley, the Coke executive who disclosed the rigged tests. Whitley, who was fired by Coke, also accused the company of using defective beverage dispensers and improper accounting.

Coca-Cola admitted no wrongdoing in the Whitley settlement. The company did praise him as "a diligent employee with a solid record" and said it was disappointed Whitley felt he had to file suit to get his issues heard. Federal prosecutors and the SEC are continuing to investigate Coke's accounting practices, the company said in a Feb. 27 filing with the SEC. Coke said in the 10-K filing it is cooperating with the investigations, while reiterating its denial of improperly inflating sales.

In January, Coca-Cola began selling Dasani in the U.K. The company immediately began facing stiff criticism from U.K. newspapers because Dasani is purified rather than spring water. The Evening Standard published an article asking "Real Thing or Rip-Off?" and the Daily Mail wrote "How Coca-Cola Is Selling Water From the Tap at 95p a Bottle."

In March, Coke had to pull Dasani from shelves across the U.K. because some samples contained elevated bromate levels. "All the capital spent on rolling Dasani out in Europe has been wasted," says Henry Asher, president of New York-based Northstar Group Inc., who has 1 percent of about $150 million in assets in Coke stock. "I frankly don't understand how something like this could happen."

To consultant Goldman, the answer can be traced back to Goizueta's unexpected death. "The whole decision making process has been messed up," he says. "There's been a lack of coherence in their judgment and decision making. One thing went wrong, then another, and when it rains, it pours."

Coca-Cola officials and board members say the company is well positioned for the future, and the turnaround under Daft in the past few years has been hidden, partly, by a series of global disasters.

At an investor meeting in New York last December, Coca-Cola officials pinned blame on "War, Famine, Pestilence, Politics & Acts of God." Among them: a labor strike in Venezuela, the U.S. war in Iraq, new government regulations on bottlers in Germany and severe acute respiratory syndrome. CFO Fayard said that a strong U.S. dollar crimped reported profit for seven straight years through 2002, as about 80 percent of Coke's $21 billion in annual sales comes from outside the U.S.

Allen, the investment banker who joined Coca-Cola's board in 1982, says that investors and analysts tend to overreact to the state of affairs at Coke. "The pendulum swings too far," he says. "We were given too much credit, and now we're being overly criticized. We're doing fine."

Though Coke stock has slumped during Daft's four years as CEO, some investors give him high marks for steering the beverage company. They blame the board for micromanaging the company and cite events in 2000, when directors turned down Daft's proposal to acquire Quaker Oats Co. "Coke looks good to us," says investor Lane. "But it would have looked even better with Quaker Oats." (See "Corporate Boards: New Rules, Old Tricks," page 68.)

The $15.3 billion purchase, which would have been Coca-Cola's biggest ever, came apart at a board meeting on Nov. 21, 2000, according to interviews with Daft and Coke board members in the Harvard Business School case study. At the five-hour meeting, Buffett-Coke's largest shareholder, with 8.2 percent of the company's stock, or 200 million shares, valued at more than $10 billion-was the most vocal dissident. The board "listened carefully, discussed it, shared different views and, in the final analysis, came to the conclusion that, given the very considerable skepticism by a number of directors in addition to the very large amount of money involved, it should not go forward," Nunn said, according to the Harvard study. "Doug does not have an autocratic view of how a board ought to be run." Nunn declined to comment for this article.

Lane says it's time some directors stepped down. "The board is an issue," he says. "Doug Daft thought he had a deal and got the rug pulled out from under him. That ought to send a signal to an awful lot of people."

In April, Rockville, Maryland-based Institutional Shareholder Services, the largest U.S. adviser to fund managers on proxy votes, recommended stockholders withhold their votes to reelect Buffett to the company's board. And the California Public Employees' Retirement System, the biggest U.S. pension fund, said it would withhold votes on its 12.7 million shares of Coke to reelect nine directors, including Buffett, because their business ties to the soft-drink maker could affect their judgment.

Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway received $633,000 from the soft-drink company for services related to rental and maintenance of aircraft in 2003, according to a report by proxy adviser Glass, Lewis & Co. Another Berkshire subsidiary, grocery and food-service distributor McLane Co., paid about $104 million in 2003 to Coca-Cola to buy fountain syrup and other products, according to a Coke filing with the SEC.

In May, before Berkshire Hathaway's annual meeting in Omaha, Nebraska, Buffett blasted ISS's efforts calling for him to step down from Coca-Cola's board and said he had no intention of doing so. "I think they're misguided in the sense that if we have $10 billion worth of stock and we buy a little Coca-Cola or sell a few things to Coca-Cola, my brain would have to be pretty confused to think that what we sell them is more important than our $10 billion," Buffett said.

Ultimately, shareholders withheld 16 percent of their votes to reelect Buffett; other directors received at least 96 percent of votes at the company's shareholder meeting. "The board has to decide whether they have a growth company or a Warren Buffett-type company that generates cash flow and buys back shares," Lane says.

Coca-Cola has already been plowing cash into repurchasing its stock. In December, Coke announced plans to buy at least $2 billion of its stock, almost 2 percent of shares outstanding, in 2004, boosting its share repurchase by one-third.

Lane wants Coca-Cola instead to use the money to buy a good business and spend on expanding what it has. "A growth company-that's what it should be," he says. "It's a great consumer brand, and it's got the whole world to sell its products to. It just needs the type of leadership that would allow it to do that." Almost seven years after the death of Roberto Goizueta, investors say, the company is still searching for that guiding hand."

ADAM LEVY is chief of the Atlanta bureau of Bloomberg News. STEVE MATTHEWS covers U.S. beverage companies in Atlanta.

adamlevy@bloomberg.net

smatthews@Bloomberg.net

FAIR USE NOTICE. This document contains copyrighted material whose use has not been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. The Campaign to Stop Killer Coke is making this article available in our efforts to advance the understanding of corporate accountability, human rights, labor rights, social and environmental justice issues. We believe that this constitutes a 'fair use' of the copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Law. If you wish to use this copyrighted material for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use,' you must obtain permission from the copyright owner.